Cleveland Dam (British Columbia, 2020)

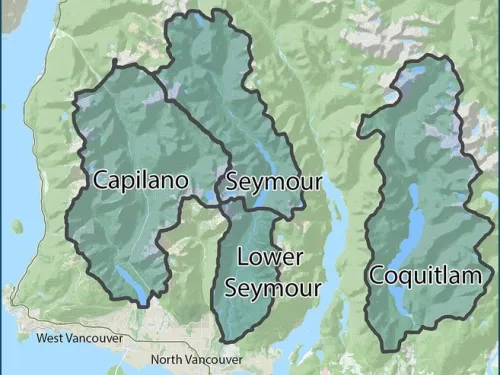

Cleveland Dam is a concrete-gravity structure that is 300 feet (91 meters) high with a crest length of 640 feet(195 meters). It is located in North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. The dam impounds the Capilano Reservoir which is in one of three major Metro Vancouver watersheds that provide drinking water to the Greater Vancouver region. The drainage catchment is 75.3 square miles in size, and the reservoir stores approximately 61,000 acre-feet at full pool [1-3]. The Capilano site was considered as a possible location for constructing a water supply dam as early as 1886, and a 1940’s investigation confirmed the feasibility of building this type of dam at that site. Construction work started in 1952 and was completed in 1954 [2, 4].

The primary control for conveyance of water downstream at the time of the incident was a drum gate, which is 70 feet (21 meters) wide and 23 feet (7 meters) tall. It is controlled remotely from a Metro Vancouver control room [5]. In the winter months, the dam’s spillway gate operates in a lower position. When heavy rains and snow melt cause an increase of water in the reservoir, excess inflows spill into the Capilano River. Each spring, the drum gate is incrementally raised to increase storage of the drinking water supply.

As discussed in more detail on the site's Lesson Learned page about the complexities of drum gates, a typical drum gate consists of a hollow steel structure (drum), hinged on either the upstream or downstream side, that is operated using the principle of buoyancy. The self-weight of the gate is overcome by buoyancy forces from water contained within a float chamber beneath the drum. To initiate spillway flows, the gate is moved to the open (down/lowered) position by releasing water from within the float chamber. There is a well-known history of operational issues and other vulnerabilities associated with drum gates. Typical concerns include: inadvertent lowering due to equipment failure or human error, puncture of the drum due to debris or rockfall, and damage due to seismic loading.

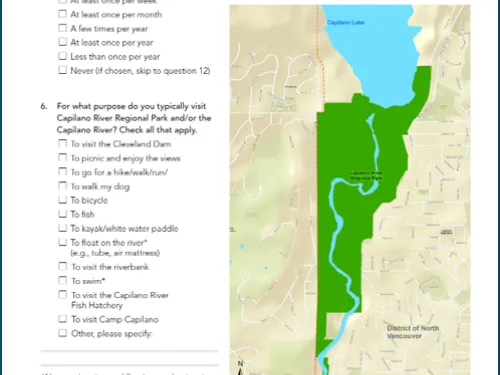

Local Geography and Public Uses of the Capilano River Watershed

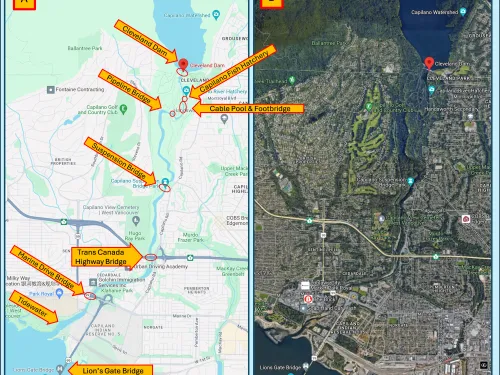

Greater Vancouver, set between the Pacific Ocean and the Coast Mountains, is renowned worldwide for its natural beauty, mild climate, outdoor recreational opportunities, and multicultural cuisine. The Cleveland Dam is located in the region’s “North Shore”, where a dense urban area reaches into dramatic tall mountains that quickly rise to more than 4,900 feet above sea level.

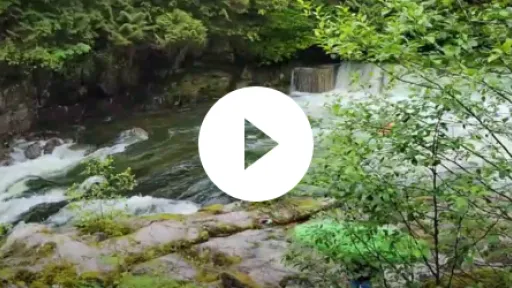

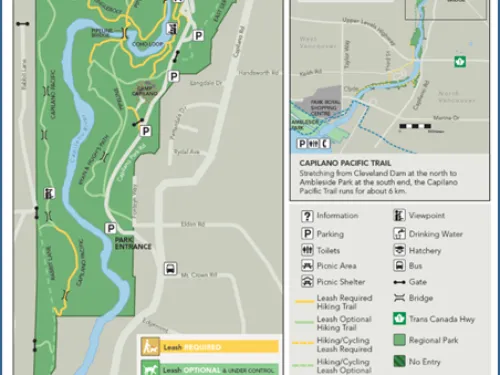

The geography of the Capilano River and Canyon is very scenic. The upper section of the river flows through a coastal rainforest of Douglas Fir and Western Red Cedar, with many trails, steep staircases and moss-covered rocks within the park area. Sections of the river flow through a narrow granite canyon with near-vertical walls that can exceed 130 feet in height. Large sandbars provide opportunities for fly fishing, and vertical evacuation in the face of quickly rising waters would not be an option along many sections of the river. Downstream towards the ocean, the river transitions into a much wider and flatter channel. The Capilano River is surrounded by residential, commercial, industrial, and harbor land uses. Many residents from the Greater Vancouver area visit the North Shore to hike, mountain bike, and ski (alpine and cross-country). They also enjoy ocean and whitewater kayaking and canoeing, river and ocean fishing, sailing, and scuba diving.

The Capilano River is rated as a Class IV rapids, and while white water paddling is not recommended, many kayakers can be seen on the river during high water [6]. The Capilano River Regional Park, which encompasses the top third of the river downstream of the dam, had almost 1 million visitors in 2022 [7, 8]. The Capilano Suspension Bridge and park, which spans the Capilano River canyon, welcomes an estimated 1.2 million visitors per year [9].

Public Safety and Flood-Related Incidents Along the Capilano River

The high levels of local, regional and tourist demands in this area present a continuing challenge for those responsible for the safe operation of the dam, for public education and safety, and for emergency services:

- The Capilano River has seen numerous incidents due to extreme flows. In 2001, four fishermen were trapped in the river when the spillway’s drum gate unexpectedly lowered [2]. Following recommendations from a consultant review, Metro Vancouver replaced the original mechanical drum gate control system with an electronic automated control system.

- Following an unexpected release from the drum gate in June 2002, additional work was carried out and included the following actions:

- Conducted a worker and public safety dam operations review and risk assessment

- Installed river level gauge downstream of the dam to detect changes in river flows

- Added redundant measuring systems and set internal alarms to monitor the reservoir level and drum gate position

- Added additional internal alarms to the drum gate control system and other dam outlets

- Developed lockout procedures for workers in the downstream river channel and on the reservoir downstream of the boom

- Added additional video surveillance at the dam and additional downstream public safety signage

- Metro Vancouver also considered but at that time decided not to install a warning system because of a number of technical challenges [10].

- Today, local emergency agencies, including the fire/rescue and police services of local municipalities and volunteer organizations like North Shore Rescue [11], are kept busy year round. In a 2021 news report, an assistant fire chief noted that their units get called out to perform rescues of fishermen on the Capilano River about 15 times a year, mostly during salmon season between September and November [12].

Drum Gate Misoperation, Inundation and Consequences, Post-Incident Investigation

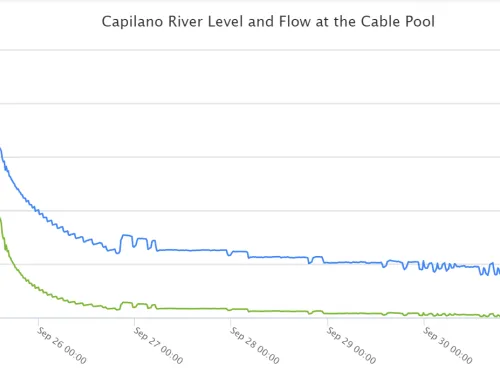

On Thursday, October 1, 2020, at or a few minutes before 1:40 pm local time, Cleveland Dam’s drum gate unexpectedly started to lower, releasing a torrent of water into the Capilano River. A river gauge just downstream of the dam recorded an increase in flows from 1,800 to 11,500 cfs (from 50 to 325 cms), and a rise in the river level from 5.9 to 13.1 feet (1.8 to 4 meters) (see the gauge chart in [13]).

Historically, the spillway drum gate operated in an automated mode and routinely raised and lowered itself as lake inflows varied, to maintain a steady reservoir level or downstream river flow. During wetter parts of the year it would be in near-continuous operation, and no alarm system was in place to notify the public when it was operating. On October 1, 2020, no public warning was issued before the drum gate unexpectedly started to lower, and people located either within the river channel or along its edge encountered rising floodwaters within minutes. An eyewitness located on an observation platform above the river described “the rumbling of a massive water flow coming towards us” and watched as those who were fishing in the river channel rushed to get away from the water’s edge. "Within three minutes there was a good three meters of water more than there had been before." There are reports that people were trapped along the river channel. Some were able to swim to shore, while local emergency services rescued others trapped on a sandbar. Two men “used trees as handholds to pull themselves up what [they] described as a vertical cliff about 15 meters (50 feet) high.” In other cases, firefighters arrived to perform rescues [13-15].

While the total number of people caught by the flows has not been determined, at least five individuals were swept downstream. Two people (a father and son) were killed. A search helicopter, kayak teams, and a Vancouver Police Department boat were dispatched to search for the son, but his body was never recovered [14].

Metro Vancouver immediately undertook a post-incident internal investigation and concluded that the primary contributing factors were deemed to be human error related to programming of the control system of the spillway gate at the dam. Three employees were dismissed from their employment with the organization [16-18].

Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program

In the weeks following the incident, Metro Vancouver initiated the Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program. Since then, a wide range of community-based engagement and dam safety planning, installation and upgrade actions have been completed (see below).

Summary Timeline of Post-Incident Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program [19-22]

January 2021

- Start of Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program

Spring 2021

- Installation of interim public-facing alarms, warning signage and new fencing along the river.

- Design and installation of new dam emergency override safety feature for the spillway gate.

Spring-Fall 2021

- Phase 1 Public Engagement and Report Out

Summer 2022- Summer 2023

- Onsite River User survey

- Preliminary Design Studies, including a Public Safety Risk Assessment of Capilano River, for the Public Warning System

- Start of reliability analysis of the Cleveland Dam

Spring 2023

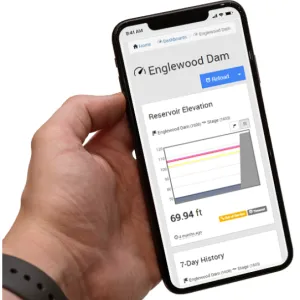

- Transition to Alertable, a 3rd-party emergency mass public-alert system and app

- Launch of river safety educational campaign and website

2024

- Detailed Design of Long-Term Public Warning System

- Start of Phase 2 Public Engagement

2025-2026

- Installation of Long-Term Public Warning System

- Address recommended actions from results of reliability analysis

References and selected copies of engagement and other documents developed by Metro Vancouver are included in the case study resources.

References

(1) Metro Vancouver. (2024). Cleveland Dam - Fact Sheet. 2024. Metro Vancouver Water.

(2) Cleveland Dam. (2024). In Wikipedia. Retrieved May 16. 2024.

(3) Metro Vancouver Watersheds. (2024). In Wikipedia. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

(6) Metro Vancouver. (2024). Seymour and Capilano River Levels. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

(7) Metro Vancouver. (2022). Regional Parks Annual Report. Metro Vancouver: Burnaby, BC.

(8) Vancouver's North Shore Tourism Association. (2023). Cleveland Dam. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

(9) Capilano Suspension Bridge. (2024). In Wikipedia. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

(10) Richter, B. & Seyd, J. (2020). Cleveland Dam disaster investigation continues. North Shore News.

(12) Richter, B. (2021). North Shore Crews Rescue Angler from Rushing Capilano River. North Shore News.

(13) Little, S. & Judd, A. (2020). Crews search for missing person after dam opened during maintenance, flooding Capilano River. Global News.

(14) Watson, B. (2020). Witness to fatal torrent released from B.C. Dam recounts moment "all hell broke loose. CBC News.

(15) Baker, R. (2022). Couple sues Metro Vancouver over deadly 2020 Cleveland Dam incident. CBC News.

(16) Canadian Press. (2020). Metro Vancouver says human error the clearest factor in fatal Cleveland Dam incident. Globe and Mail.

(17) Richter, B.(2020). Fatal Cleveland Dam disaster blamed on human error. North Shore News.

(18) Dunphy, M. (2020). Three workers fired in aftermath of Cleveland Dam incident that resulted in one dead, one missing. The Georgia Straight.

(19) Burton, T. & Anthony, V. (2024). Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program [Memo to the Water Committee]. Metro Vancouver Water.

(20) Metro Vancouver. (2021). Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program Discussion Guide: Phase 1 Public Engagement - Interim Public Warning System. Metro Vancouver Water.

(21) Metro Vancouver. (2021). Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program: Phase 1 Public Engagement - Summary Report. Metro Vancouver Water.

(22) Metro Vancouver. (2024). Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

(23) Metro Vancouver. (2024). Photos of Cleveland Dam with its spillway drum gate open and closed. Metro Vancouver Water.

(24) Metro Vancouver. (2022). Capilano River Regional Park. Metro Vancouver Parks.

An independent review of this case study was provided by Metro Vancouver Water Services staff. Their contributions are gratefully acknowledged. This case study was also peer-reviewed by Cory Miyamoto, PE, CA DWR, Division of Water Safety.

Lessons Learned

Dam incidents and failures can fundamentally be attributed to human factors.

Learn more

Dam owners, engineers and regulators need to address public safety at dams.

Learn more

Downstream flooding can be caused by spillway flows that exceed channel capacity or as a result of reservoir misoperation.

Learn more

Drum gates are complex mechanical systems that must be carefully operated and maintained.

Learn more

Early Warning Systems can provide real-time information on the health of a dam, conditions during incidents, and advanced warning to evacuate ahead of dam failure flooding.

Learn more

Gates and other mechanical systems at dams need to be inspected and maintained.

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn more

Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program

Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program

Metro Vancouver – Cleveland Dam Safety Enhancements Program