Kinugawa Levee at Joso (Japan, 2015)

Background

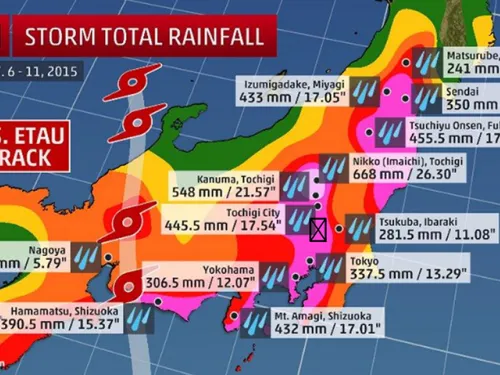

Beginning around September 6, 2015, Tropical Storm Etau (Typhoon No. 18) together with Tropical Depression Kilo (Typhoon No. 17) began dropping excessive rainfall across northeast Japan. The interaction of the two systems caused them to stall and concentrate rainfall in a narrow band over the Kinugawa watershed. Some places accumulated over 2 feet of rain in a few days. The steep terrain let loose in mudslides, landslides, and flash floods. Four upstream flood control reservoirs in the watershed all had spillway flows sending a significant flood down the Kinugawa River.

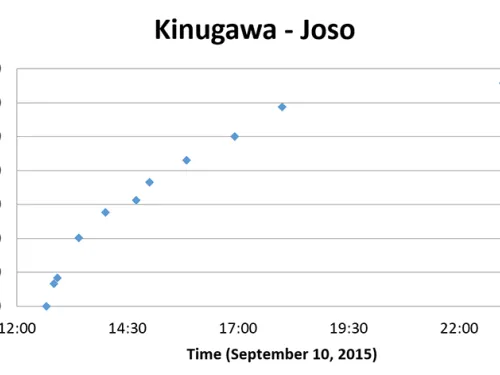

The Kinugawa River is a major tributary of Japan’s most important river, the Tone River. They confluence about 20 miles northeast of Tokyo. On September 10th, the Kinugawa River began to overtop its natural banks in a few places and then around mid-day breached the east bank levee in Joso-shi, Ibaraki Prefecture. The levee is roughly 12 feet high and breached by overtopping of less than 2 feet. It had also been experiencing some sand boils on the same reach. The breach flow and other out of bank flows combined to inundate an area of over 15 square miles.

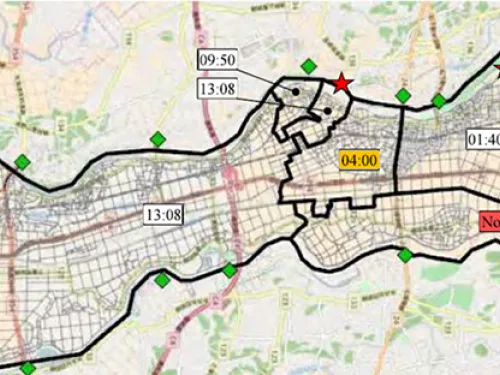

Timeline

Evacuation warnings began shortly after midnight and continued into the early morning hours for sections of the expected overflow area, but the area near the eventual levee breach did not receive an evacuation order until after the breach occurred.

At the time of the breach people were aware of high water in the river, but did not seem very concerned about a levee breach. Around 7:00 AM the river began overtopping a natural high bank that may have been degraded by a recently built solar farm. This location is roughly 2 miles upstream of the breach. Floodwaters moved south through the basin and triggered a response from rescue agencies and fire departments. In addition, multiple news agencies sent helicopters to cover the event on live television.

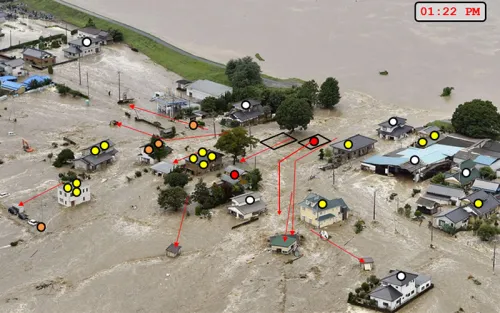

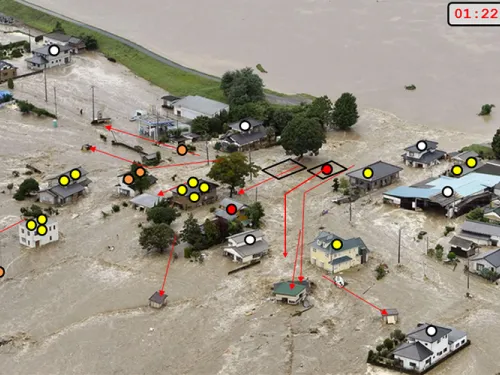

At 12:50 pm, the levee breached directly into a residential neighborhood. Most homes in the breach zone were still occupied. The deep and swift water washed away homes and other buildings, some with people inside or on the roof. The breach grew to 600 feet wide in 5 hours. Aerial rescues saved dozens in the breach zone within a couple hours, while several hundred were rescued by boat or helicopter in the flooded area. Tragically, two people were confirmed dead. Heroic efforts prevented this number from being much larger. The early flooding upstream likely contributed to the rapid response time of helicopters to the breach zone. By the next morning, September 11th, breach flow had subsided and cleanup and damage assessments were underway. Within two weeks the levee was repaired to full height.

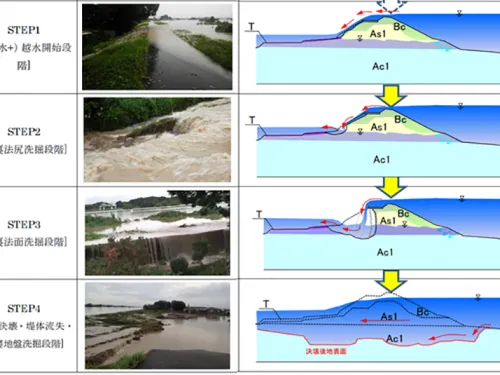

Failure description

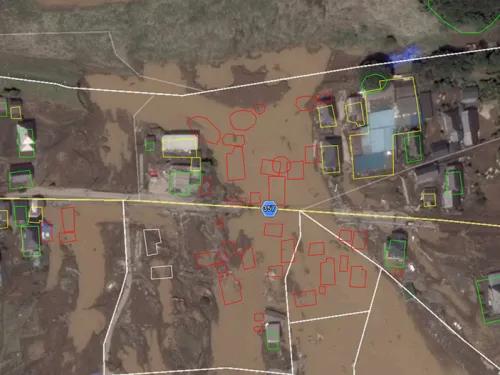

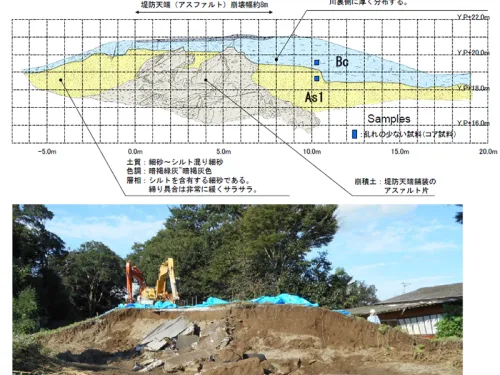

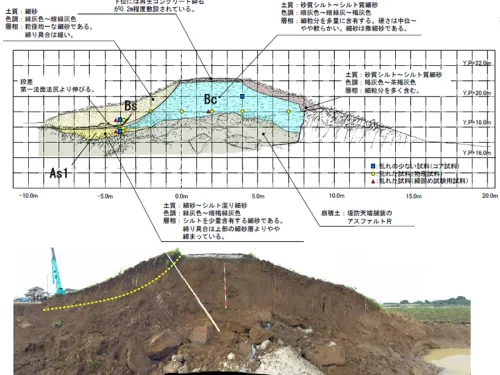

The levee was raised by the addition of silty cohesive materials on top of the naturally existing sandy overbank deposits. It was overtopped by around 1 to 2 feet maximum and eroded the back side leading to breach within two hours. The initial breach location grew within minutes to 85 feet wide and scoured 6 feet below grade to the hard clay foundation. It was 200 feet wide within a half hour and flowing between 8 and 15 feet/second and around 5 to 10 feet deep. Flow depths and velocities were highly impacted by obstructions such as large trees, buildings, and barriers until they were undermined or washed away.

Lessons Learned

1. Evacuation orders should consider the expected movement of floodwaters, and be coordinated with neighboring jurisdictions as early as possible. Warnings were sent haphazardly and neglected several areas at risk. Local shelters were opened in areas that should have been expected to flood and were indeed inundated, trapping many people. Agreements had to be reached during the emergency with neighboring municipalities to shelter evacuees out of the flooded area.

2. Video and photos taken during the breach event were very valuable to post-event analysis of the hazard and consequence research including breach erosion progression. Efforts should be made to collect this information while it is fresh following dam and levee failures to aid in analysis later.

3. Although National government agencies knew of the levee and river status before and during the event, the local government agency was not able to evacuate residents in time. This was due to both inadequate communication between agencies, and lack of capability at the local level to interpret the available information and take action. Since the incident, the Federal government has taken the initiative to communicate river conditions directly to impacted residents.

4. A detailed breach and flood hydraulics model, coupled with an agent-based evacuation and consequence model provided valuable insight to the hazard progression and damages. They were calibrated with video, photo, and other observations such as stream gages. These tools may provide value for planning efforts by increasing understanding of the impacts of inadequate warning time as it relates dynamically to the progression of the flood.

References:

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by Bill Johnstone, P.E., Spatial Vision Group, Inc.

Lessons Learned

Emergency Action Plans can save lives and must be updated, understood, and practiced regularly to be effective.

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn more

1st Kinugawa Levee Investigation Committee Report

A Guide to Public Alerts and Warnings for Dam and Levee Emergencies

Kinugawa Levee Investigation Committee Final Report

Levee Breach Consequence Model Validated by Case Study in Joso, Japan