Walnut Grove Dam (Arizona, 1890)

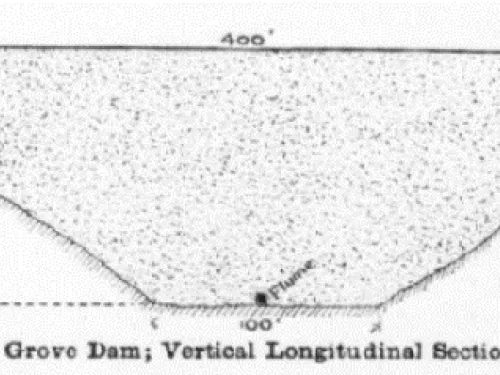

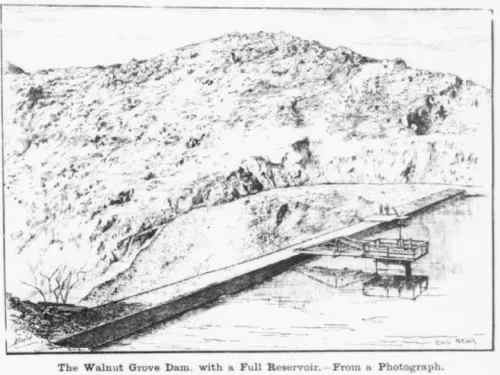

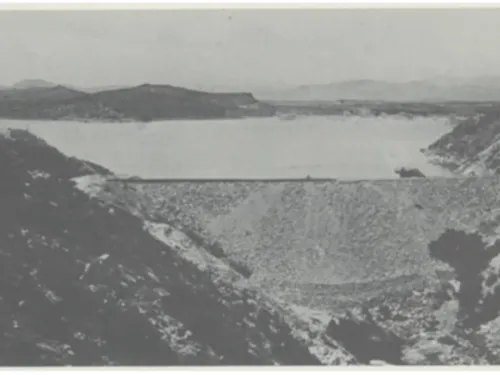

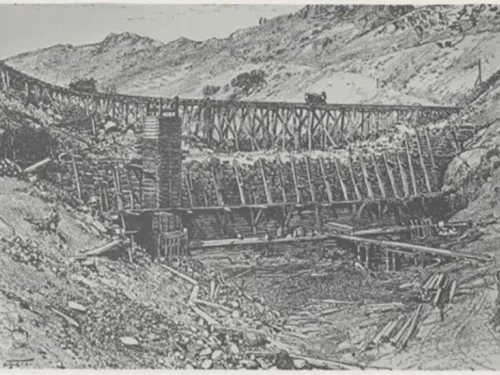

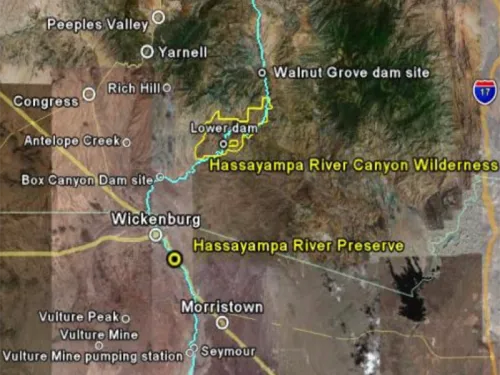

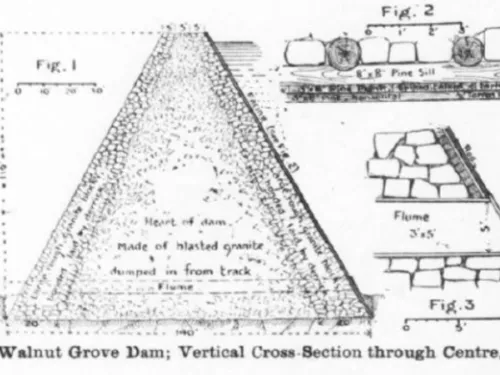

Walnut Grove Dam was constructed at a site approximately 20 miles northeast of Wickenburg, Arizona. Gold had been discovered in the area and a New York Investor, Wells H. Bates, wanted a dam built in order to supply water for hydraulic mining. He acquired the mining rights and then hired William P. Blake, a renowned geologist, to design and construct the dam. Blake worked with his sons on the dam beginning in February 1886. However, he was fired shortly after beginning work. He was replaced by E.N. Robinson a civil engineer from San Francisco. Robinson was unable to salvage any of the construction that Blake had begun and no design documents were available, so he largely started over. One of the aspects Robinson called for was a larger spillway. However, after Robinson had only been on the job for 4 months, he was fired. It is unclear exactly why, but he was then replaced by one of the New York Investors brothers who had no engineering or construction experience.

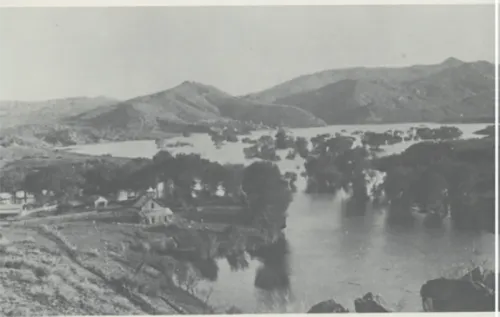

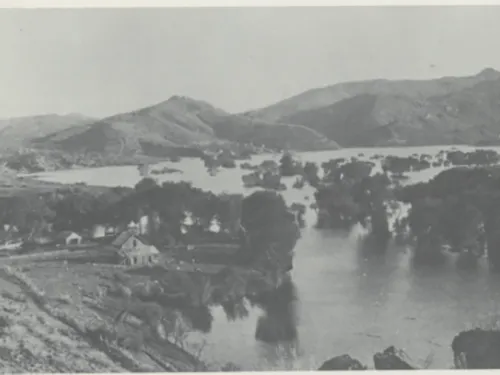

Managing a dam construction project from over 2,000 miles away presented many challenges. During the construction there were frequent complaints about low pay, poor oversight and quality control, an untrained work force, and high construction and design costs – by the time the project was complete there would be 5 different chief engineers on the job, each serving as superintendent (one would go on to become Governor of Arizona). Robinson’s larger auxiliary spillway would never be constructed. After he left the project, the size of the spillway was debated, but ultimately a much cheaper, smaller spillway was constructed. Large storm events occurred in 1889, the year after completion, and made the need to expand the spillway clear. Work was being done on the spillway when it began to rain on February 16, 1890. It would rain on and off until February 22. This rain-on-snow flood event caused the dam to overtop, leading to failure on February 22, 1890. The event was estimated by Liggett in 2010 using USGS regional regression methods to have a flood flow frequency of 1 in 25 years.

There was an onsite superintendent who saw the dam being overtopped. He sent Dan Burke on horseback to warn people downstream. Dan however stopped at a local pub and got drunk and never warned the downstream residents. The first settlement hit was a worker’s camp that was working on downstream infrastructure to make the hydraulic mining possible. Over fifty people at the camp were dead or missing, leaving very few alive. The flood wave destroyed homes, farms, mines and took with it approximately 100 lives. There were several lawsuits related to both the dam, its construction and its failure, all against the company that owned and built the dam. Given how many chief engineers had been onsite and the times when there was no superintendent onsite, there were many people that shared in the work to point fingers at. Ultimately, the courts could not agree on where to place the blame and none of the lawsuits were successful.

There were several times that plans were put in place to rebuild the dam, but none were successful.

References:

(1) Dill, D. B. (1987). The Walnut Grove Dam Disaster of 1890. The Journal of Arizona History, 28(2), 283-306. Arizona Historical Society.

(2) Liggett, J. (2010). Arizona’s Worst Disaster, The Hassayampa Story 1886-2009. Pathfinder Publishing.

(4) Willis, H. B. (1976). Evaluation of Dam Safety Engineering Foundation Conference Proceedings. American Society of Civil Engineers.

(6) Desmond, D. (2017). 1890: The Dam, The Drunk, & The Disaster. PrescottAZHistory.

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by Paul Risher, P.E., HDR.

Lessons Learned

All dams need an operable means of drawing down the reservoir.

Learn more

Dam incidents and failures can fundamentally be attributed to human factors.

Learn more

Emergency Action Plans can save lives and must be updated, understood, and practiced regularly to be effective.

Learn more

High and significant hazard dams should be designed to pass an appropriate design flood. Dams constructed prior to the availability of extreme rainfall data should be assessed to make sure they have adequate spillway capacity.

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn more

The Walnut Grove Dam 1890 Failure: The Worst and Most Forgotten Disaster in Arizona History