Wanapum Dam (Washington, 2014)

Wanapum Dam is a composite dam, consisting of both earth embankment and concrete gravity sections, that spans the Columbia River near Vantage, Washington. Extending more than 8,600 feet from bank to bank, it includes left and right earth embankments, left and right concrete gravity sections, a concrete gravity spillway with 12 radial gates, 6 future unit intake monoliths, and a 10-unit powerhouse. The dam’s primary use is hydropower. Wanapum dam is 186.5 feet tall with a 14,680-acre reservoir storing 693,600 acre-feet of water. The dam is owned by Grant County Public Utility District (GCPUD), which also owns and operates the Priest Rapids Dam on the Columbia River. Wanapum Dam is named in honor of the Wanapum people, a Native American tribe who have historically lived along the river (Wanapum means “river people”).

The 12-bay, radial-gate, concrete spillway on Wanapum Dam is 832 feet long and located at approximately the right third of the dam (looking downstream). The gates are supported above the spillway section on reinforced concrete piers, while the spillway itself consists of multiple monoliths separated by vertical contraction joints. Each radial gate is 50 feet wide by 67 feet high, with a capacity of 117,000 cfs, for a combined total spillway capacity of approximately 1,400,000 cfs. When the dam was constructed in the early 1960’s, these gates were the tallest in the world.

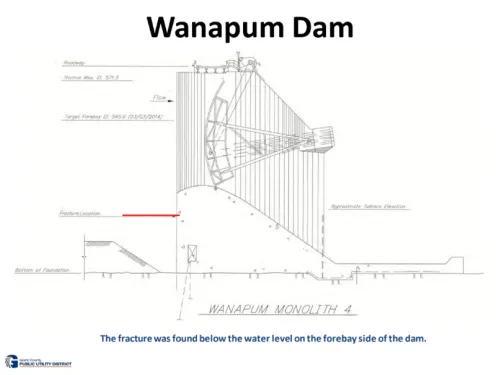

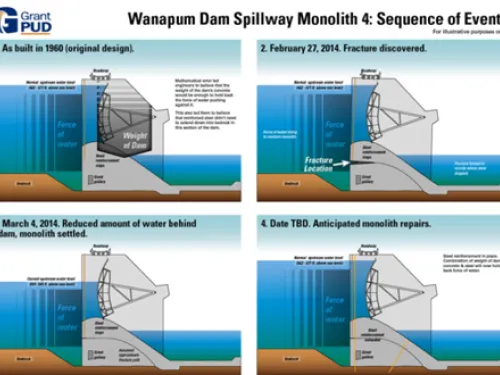

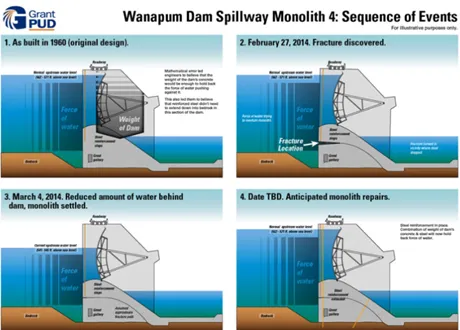

Beginning in early to mid-February of 2014, Jim Claussen, a hydro mechanic for GCPUD, made a series of unusual observations. First, he observed leakage out of two adjoining gates on the downstream side of the spillway. Then, after the gates had gone through a spill cycle, he observed the leakage was getting worse, “creating mist you could see from...the highway coming into the dam (GCPUD, 2020).” Once he got to the dam crest to look at the leakage from that vantage point, he observed a pronounced curve in the alignment of the roadway deck curbs and handrails that span the spillway. He and his accompanying coworkers at the time began to suspect that a large mass of concrete had moved. This was confirmed by divers on February 26, 2014, who observed a 2-inch-wide, 65-foot-long crack that spanned the full length of Monolith 4 at the concrete lift joint.

Immediately GCPUD began to draw the reservoir down, lowering it to 26 feet below normal pool by the first week in March. This reduced the total overturning moment caused by the hydrostatic uplift pressure exerted via the crack and the horizontal pressure on the face of the monolith, allowing the counteracting moment from the weight of the concrete to prevail and the crack to close. In the meantime, a team of engineers was assembled and began working to find the cause of the crack. After 11 weeks of pouring over historical documentation, the engineers concluded that errors in the original design calculations and late changes to the final spillway design led to a condition that generated tensile stresses in the concrete at the upstream face.

When the engineers examined field calculations completed during construction and recalculated the formulas, they found the mass of the concrete alone was not enough to resist the load of the reservoir water acting on it. The design should have contained more concrete and/or reinforcing steel to resist the overturning moment. In addition, construction documents indicated there may have been problems curing the concrete on this section due to unusually hot ambient temperatures the weekend of the pour. Hot curing temperatures would have led to a weak construction joint, another factor contributing to instability. Finally, when the dam was originally designed, it was not common practice to account for stresses in the concrete due to seasonal temperature variations. Finite element analyses indicated that significant, seasonal, tensile stresses develop in the upstream face of the spillway, and that there is a full stress reversal (compression to tension) that occurs on an annual basis. This cyclical behavior could have led to a loss of tensile strength due to fatigue and micro-cracking.

Investigators believed the crack may have initiated years prior and spread gradually, ultimately allowing enough seepage into the fracture to cause uplift pressures that, when added to reservoir pressure on the upstream face, caused an overturning moment that the weight of the concrete itself was unable to overcome. After 50 years in operation, the crack eventually formed. Had GCPUD known of the potential instability issue earlier, the spillway could have been reinforced, reducing the likelihood of the crack formation.

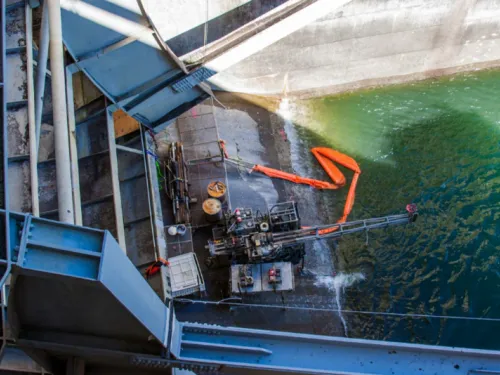

Remediation consisted of drilling lift joint drains above the gallery to reduce uplift pressure resulting from seepage within the body of the dam. In addition, post-tension anchors were installed in each spillway monolith to mitigate against potential stability issues. In all, thirty-five (35) 61-strand tendon anchors, in 16-inch diameter boreholes with lengths of up to 260 feet, were installed through the spillway piers. An additional sixty-nine (69) 3-inch-diameter (majority), solid-bar anchors were installed through the ogee section. Cracks were repaired in Monoliths 2 and 4 to reduce seepage, decrease water pressure, and improve stability. The reservoir was restored to full pool in March 2015, just over one year after the issue was discovered.

While the immediate threat to the public was considered low at the time of the incident, many important lessons that could help prevent future incidents and failures can be learned. One of the most important is the awareness of the always-present human factor. Once operations personnel had gathered enough evidence in the field to indicate what had occurred, some initially still had a hard time convincing themselves that a section of concrete that big could move. As Mr. Claussen stated in an interview describing the incident, “That was the hard thing, once we saw the problem, to try to get your own mind to accept that that has moved or something that size is moving, that amount of concrete, that weight, how it can move. It takes a while for your own mind to come to grips with that.”

References

(1) Grant Public Utility District. (2020). Wanapum Spillway Discovery [Video]. YouTube.

(2) ASDSO. (N.D.). Dam Incident Database. Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

(4) Occupational Health & Safety. (2014, March 3). Engineers Monitoring Crack in Columbia River Dam.

(6) Chappell, B. (2014, March 4). Divers Find 65-Foot Crack In Columbia River Dam. NPR News.

(7) King, A. (2014, May 13). Crack In Wanapum Dam A Symptom Of Several Big Problems. NWNews.

(9) I Build America. (N.D.) Project: Wanapum Dam.

(11) HDR Engineering. (2014). Forensic Investigation and Root Cause Analysis, Spillway Monolith No. 4 Displacement, Wanapum Development, Priest Rapids Hydroelectric Project.

This case study was peer reviewed by Zach Ruby, P.E. (Grant PUD).

Lessons Learned

A complete and thorough dam record is essential.

Learn more

All dams need an operable means of drawing down the reservoir.

Learn more

Concrete gravity dams should be evaluated to accommodate full uplift.

Learn more

Dam incidents and failures can fundamentally be attributed to human factors.

Learn more

Forensic investigations are needed for major dam failures and incidents in order to determine the history of the contributing physical and human factors, and the culminating physical failure modes and mechanisms.

Learn more

The Study of Past Dam Failures and Incidents is Essential for Keeping Today’s Dams Safe.

Learn moreAdditional Lessons Learned (Not Yet Developed)

- The human factor can come into play as the mind sometimes tries to work against evidence of a developing incident, especially when the evidence is subtle and may not all point in the same direction. This incident highlights the importance of diligent observation and critical review of monitoring data when even the smallest anomalies come to light. Note, a challenge in the case of Wanapum Dam was that the survey data indicated the monolith was moving, but the piezometers and foundation drains did not.

- Out-of-the-box thinking and brainstorming are critically important to the Potential Failure Modes Analysis (PFMA) process, as is not accepting the analysis results as definitive and comprehensive, leaving open the possibility of previously-not-considered scenarios. In the case of the Wanapum Dam PFMA, failure of the concrete-rock interface was identified, but failure at a spillway monolith lift joint was not. In addition, things such as standard of practice at the time of design or construction; the availability of new information, knowledge, or understanding; fatigue over time from cyclical loading, corrosion of reinforcement, environmental factors, etc. should be considered during a PFMA.

- Stringent quality control is important in design calculations, as well as diligence when considering design changes, to make sure the design is, and remains, sound.

- Quality control during construction is important to avoid low-quality and/or strength in-place material that does not meet design assumptions.

- Engineers should avoid complacency and always remain inquisitive. Do not assume the previous engineers got it right or that all calculations and analyses were captured in final recorded documents. The calculation of interest in this case was done in the field during construction and only found in a basement repository during the data collection effort for the Root Cause Analysis. There is value in periodically revisiting calculations, analyses, and assumptions that can have significant impacts on the safety of the structure, especially as tools, methods, and engineering judgment continue to improve and advance.