Wind loading can have a significant impact on dam safety.

Wind is often treated as background noise in dam safety work as most of our attention goes to other design criteria such as hydrologic loading, seismic loading, ice loading, slope stability. Yet several notable incidents and failures show that wind driven waves, can be primary drivers of dam risk.

The 1972 Kingsley Dam incident in Nebraska, the 1951 Lily Lake Dam failure in Colorado, and the 1926 and 1928 Lake Okeechobee disasters in Florida are stark reminders that wind can generate enough wave action to damage or even fail large embankment systems. The Lake Okeechobee events also highlight a second theme: during major wind and storm events, access, and communication can all degrade just when they are needed most.

This lesson learned uses those events as context and ties them to existing guidance on freeboard during normal and flood conditions, embankment slope protection, gate loads, and emergency planning. The goal is to remind practitioners that wind loading is a key design and dam safety consideration, not a secondary consideration.

Case Studies

Kingsley Dam, Nebraska (1972): A Wind Driven Near Miss

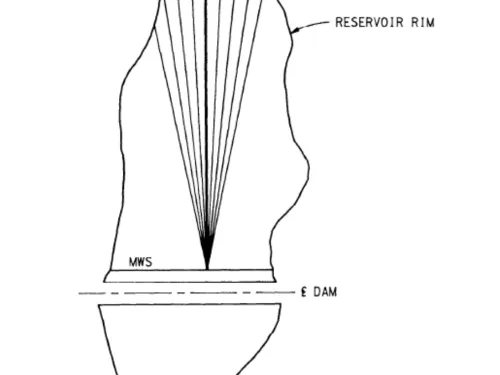

Kingsley Dam is a 163 foot high, 3 mile long hydraulic fill embankment that forms Lake McConaughy on the North Platte River in western Nebraska. On April 30–May 1, 1972, the reservoir was near its normal full level when a prolonged spring storm produced strong, sustained winds blowing directly down the long fetch toward the dam. Reported winds were on the order of 30 to 40 miles per hour (mph), with higher gusts, and significant waves on the order of 10 feet developed on the reservoir (Gokie and Drain, 2025).

Those waves repeatedly attacked the upstream slope, eventually dislodging the riprap and bedding over several sections of the dam while spray, droplets and sheets of water that travel above the runup elevations, overtopped the parapet, wetting the embankment crest.

Once the rock protection was removed, wave action rapidly eroded the underlying sand shell. Large craters formed in the upstream face, some extending close to the parapet wall along the crest. Continued erosion eventually undermined about 440 feet of parapet, which collapsed into the lake (Gokie and Drain, 2025).

Importantly, none of this was driven by an extreme inflow event. The reservoir elevation was high but within the normal operating range. There was no flood overtopping in the traditional sense. The threat to the dam came almost entirely from wind generated waves operating on a high, but otherwise routine, pool level. Operators lowered the reservoir and placed temporary protection while the storm was still in progress. Post incident evaluations led to modifications of the upstream slope protection, changes in reservoir operating rules, and a much greater appreciation of the dam’s vulnerability to wind wave loading (Gokie and Drain, 2025).

The Kingsley Dam incident is a classic “near miss”: there was no breach, but the situation was critical. The erosion pattern shows that only limited additional degradation might have been required to initiate a progressive failure of the upstream shell and core. The event demonstrates that even large, well known embankment dams can be vulnerable to wind wave hazards during normal pool levels.

Lily Lake Dam, Colorado (1951): A Wind-Induced Embankment Failure

Lily Lake Dam is a small, 245‑foot‑long, 15‑foot‑high embankment dam in Rocky Mountain National Park, impounding an 18‑acre natural lake just upstream of Colorado State Highway 7 and the town of Estes Park. The dam failed in May 1951 while under private ownership. The post‑incident investigation concluded that the failure was initiated by wave action generated by high winds across the relatively short but effective fetch of Lily Lake. Witnesses reported “terrific lashing waves” 2 to 3 feet high striking the upstream face and crest; these waves progressively eroded a hole through the earthfill dike before dawn, releasing roughly 75 acre‑feet of water. The breach outflow overtopped Highway 7, lifting and carrying the paved surface, trees, and boulders into the downstream canyon, and flooding two homes and a county road, though fortunately without loss of life (Baker, 2014).

When the National Park Service later assumed ownership, the 1951 wind‑wave failure was treated as a key piece of evidence that wind loading on the reservoir could credibly initiate an embankment failure. In 2009, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) performed a screening‑level risk study that identified hydrologic overtopping as the dominant risk driver, with seismic liquefaction and several internal erosion modes also plotted in the high‑risk region of the matrix. Overtopping was estimated to occur at about the 1:100 annual‑chance flood, with failure progressing through erosion of the downstream slope and crest. Building on that screening, a 2012 Issue Evaluation explicitly added a separate failure mode for “wave erosion of the crest” to reflect the historical 1951 wind‑induced breach. In the updated risk matrix, wave‑driven crest damage and overtopping are tracked alongside flood overtopping, seismic, and internal erosion modes, ensuring that wind‑wave action remains visible in portfolio‑level risk decisions and in the prioritization of risk‑reduction measures at Lily Lake (Baker, 2014).

Design and operational decisions at Lily Lake since then have been framed against that combined hydrologic and wind‑wave risk picture. Reclamation completed a new PMF study in 2011, which showed prolonged but relatively shallow overtopping in a PMF event. The National Park Service elected to “repair to conservative levels” by designing for the full PMF and armoring the crest and spillway with articulated concrete block (ACB) overtopping protection, rather than relying solely on additional analyses to refine estimated probabilities. During the September 2013 Colorado Front Range flood (greater than a 1:1,000 annual‑chance rainfall at Lily Lake), the dam experienced high, sustained spillway flows; the ACB system performed as intended, with only superficial gravel loss and minor erosion in downstream appurtenant areas (Baker, 2014), validating the decision to treat both flood overtopping and wind‑wave‑initiated crest erosion as credible contributors to overall risk.

Lake Okeechobee (1926 and 1928): Wind, Storm Surge, and Catastrophic Loss of Life

In the early 1900s, low agricultural levees were constructed in segments along the south and southeast shore of Lake Okeechobee, the second largest, in surface area, freshwater lake in the United States covering approximately 730 square miles (~467,000 acres). These dikes were on the order of 4- to 6-feet-high, built largely from local soil materials, and never intended to withstand the combined effects of a major hurricane’s storm surge and waves (NWS, undated).

The Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 drove a storm surge across the lake, overtopping and breaching portions of the west side levee and causing hundreds of fatalities (Lloyd’s of London, 2006). Two years later, the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane produced even more extreme conditions. As the eye of the storm passed just south of the lake, sustained winds well over 100 mph pushed water toward the southern shore, building a surge and set up that overtopped the small levees by several feet. Floodwaters several meters deep swept through communities like Belle Glade, Pahokee, and South Bay, killing on the order of 2,500–3,000 people (USACE, undated). The dominant mechanisms were wind and storm surge. Rainfall was heavy, but the catastrophic flooding around the lake was driven by hurricane force winds pushing the lake surface against the shore, increasing water levels and generating large waves on top of that setup. The low levees had little freeboard, poor cross sections, and limited erosion resistance. Once overtopped, they breached in multiple locations.

In response, Congress authorized a comprehensive federal flood control project. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers designed and constructed what became the Herbert Hoover Dike, a 143 mile earthen dam system with much greater crest height, more robust cross sections, gated structures, and an integrated regional flood control network (USACE, undated). This history is part of why the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) now treats the Herbert Hoover Dike as a high hazard dam, not simply a levee ring. Lake Okeechobee illustrates how wind, storm surge, and waves can be risk drivers for large, shallow reservoirs in hurricane prone regions. It also serves as a reminder that “agricultural” levees or small dikes may be completely inadequate once population at risk grows and wind driven hazards are fully recognized.

Wave Runup and Wind Setup in IDF and Freeboard Evaluations

FEMA’s Federal Guidelines for Selecting and Accommodating Inflow Design Floods define freeboard as the vertical distance between the reservoir water surface and the dam crest and explicitly recognize wind generated wave runup and wind setup as important contributors in freeboard design.

Wave runup is the vertical height that individual waves climb above the stillwater level at the dam, while wind setup is the increase in mean water level at the windward shore caused by the shear stress of wind acting over a long fetch.

FEMA recommends that freeboard for wind wave action be based on the significant wave height and that the sum of wind setup and wave runup be used to determine the required allowance for this component of freeboard.

The guidelines also recognize that the “worst wind” and the “highest water level” may not coincide. Maximum winds are unlikely during the brief period when the pool is at its peak IDF stage, while normal pool levels persist for extended periods and can be exposed to the true maximum winds. Designers are therefore encouraged to look at combinations: winds appropriate for the brief period at maximum IDF pool for minimum freeboard, and maximum winds at normal pool for normal freeboard.

Additionally, the USACE, in EM 1110 2 2300 provides similar direction. Freeboard must be sufficient to prevent overtopping by wind setup, wave action, and earthquake effects, and crest elevations should incorporate allowance for post construction settlement. Kingsley Dam and Lake Okeechobee both illustrate what happens when this integration is incomplete. At Kingsley, a high but not extreme pool, combined with long fetch and high winds, produced waves that exceeded the capacity of the existing slope protection. At Lake Okeechobee, low levee crests with essentially no margin above hurricane storm surge and wave runup proved fatal.

Embankment Vulnerability and Slope Protection Under Wind Wave Loading

For embankment dams, the upstream slope is the first line of defense against wind driven waves. Slope armoring such as riprap, soil cement, ACBs, etc. are not surficial, but structural elements that must be designed for site specific wave conditions.

USACE, Reclamation, and the National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) all provide procedures to estimate design wave height based on design wind speed, duration, and effective fetch, then translate that wave height into required rock size, gradation, and thickness. Reclamation’s Design Standards No. 13- Embankment Dams, Chapter 7, provides specific guidance for designers.

Both DS 13 (Reclamation) and TR 69 (NRCS) emphasize that many factors control riprap stability: wind velocity, direction, and duration; wave height and period; reservoir geometry; and the details of riprap and bedding. Reclamation notes that the band of slope between the bottom of the active conservation pool and the top of joint use storage tends to see the most severe wave conditions and therefore warrants the most robust protection.

USACE similarly classifies slopes into exposure classes, with the “Class I” zone (frequently exposed to normal operating levels) designed for rarer, more severe winds than the higher, less frequently wetted zones. Kingsley Dam shows what happens when actual conditions exceed design assumptions. The 1972 storm produced waves that, combined with long attack duration and perhaps some prior degradation, dislodged the riprap and allowed wave energy to directly impact the erodible shell. Post incident measures included heavier rock, revised bedding and filters, and a re evaluation of design winds and fetch (Gokie and Drain, 2022).

Alternative upstream protections such as soil cement can perform well under wave loading but bring their own freeboard and detailing requirements. Reclamation’s soil cement design standard notes that wave runup on stair-stepped soil cement can be about 50 percent greater than on riprap, which in turn may require higher crest elevations. Soil cement also behaves as a rigid facing, which can crack or break into slabs under repeated wave action if layer bonding and thickness are inadequate.

For both wind-wave runup/setup analyses and upstream slope protection design, wind speed, direction, and probability relationships are needed. Often regulators will specify a windspeed loading criteria; however, when no specific loading is prescribed, practitioners need to develop these relationships.

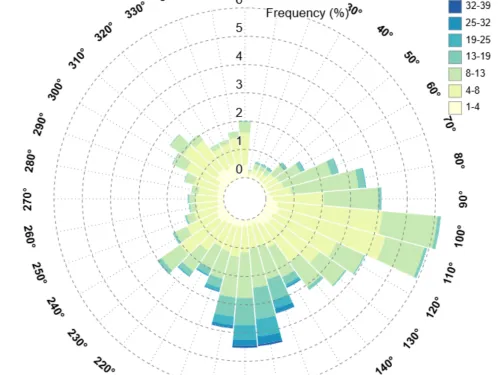

The necessary relationships can be developed by compiling and analyzing regional wind data from available monitoring stations to derive exceedance probability curves, which are used to estimate representative overland wind velocities. These frequency velocities would then be converted to over-water velocities using published guidance. In the U.S., gage data for a given site may be available from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) or other data providers. A fairly common and useful method to visualize windspeed, direction, and probability relationships is via wind rose diagrams, circular charts showing the frequency of wind direction and speed at a specific location such as a gaging station.

Horizontal Wind Loads on Gates and Concrete Structures

Wind generated waves do not only act on embankment slopes. They can also impose horizontal, cyclic forces on gates and concrete structures. USACE EM 1110-2-1603 notes that horizontal forces on crest gates can result from both waves and ice and that wave forces should be considered wherever fetch is sufficient to generate substantial waves.

These loads may not control the structural design of large monoliths or piers, but they can be important for gate leaf design, hoist sizing, and operational reliability. Under high reservoir levels and high winds, waves can cause gate vibration, fluctuating hoist loads, and difficulties in fully opening or closing gates. For radial and vertical lift gates that are already subject to complex hydraulic loads during operation, wave induced forces can add another layer of uncertainty. In severe storms, spray and overtopping around gate decks and access bridges can also impede safe manual operation—especially in winter freezing conditions. When gate reliability is part of the dam’s ability to pass the IDF or prevent overtopping, wind wave loading on gates can become a significant dam safety concern. Additionally, wind events can result in down timber and rafts of logs and debris that get pushed towards a dam’s gates and/or spillways; these mats can strain log booms or cause blockage of spillways (if a boom fails or none is present), decreasing their capacity to discharge flood flows.

Wind, Storm Surge, and Hurricane Prone Reservoirs

For coastal and near coastal reservoirs, wind loading cannot be separated from the broader problem of hurricane storm surge and seiches. Hurricane winds can raise water levels by several feet through setup, and a decrease in atmospheric pressure can drive long period surface oscillations in large, shallow lakes.

The Lake Okeechobee experience is instructive. Historical analyses and modern simulations by the National Weather Service show that hurricane force winds in 1928 pushed lake water against the southern levees, overtopping 4–5 foot embankments and flooding surrounding communities to depths of several meters (Lloyd’s of London, 2006 and NWS). The Herbert Hoover Dike, by contrast, has typical crest elevations around 30 feet and incorporates much more robust cross sections to reduce the risk of catastrophic failure during extreme hurricanes (USACE).

For other hurricane prone dams and levees, similar principles apply:

- Storm surge and wind setup can combine with riverine floods, raising both reservoir and tailwater levels.

- Large, shallow reservoirs with long fetches, and relatively flat surrounding topography can develop significant waves under hurricane force winds, even without flood inflows. These geographic contributors can be amplified when the embankment is oriented near-perpendicular to the prevailing wind direction.

- Freeboard and slope protection must be designed using realistic hurricane wind fields and durations, not just local thunderstorm winds.

FEMA’s freeboard guidelines explicitly note that freeboard combinations should consider the reasonable simultaneous occurrence of pool elevation, wind, and other factors and that, in some cases, intermediate combinations of wind and water level (for example, in dedicated flood control pools) may control the design (FEMA, 2015).

Wind Impacts on Access, Operations, and Warning Systems

Wind does not only act on dams, Extreme storms and winds can also degrade the systems we rely on to detect problems, operate the dam, and warn downstream populations.

High winds, blowing spray, and floating debris can make crest access hazardous or impossible, just when operators might wish to inspect the upstream slope or operate manual equipment. Prolonged wind events often coincide with widespread power outages, downed communication lines, and blocked roads. At Lake Okeechobee in 1928, roads became impassable and communications were “nearly wiped out” in many impacted communities, contributing to the lack of timely warnings and coordination (USACE, undated).

Modern emergency action plans (EAPs) generally recognize that the most critical dam safety scenarios often occur during large regional storms. USACE EM 1110-2-2300 provides guidance on failure mode analysis and emergency planning emphasizes the need to understand how project performance might degrade and what information is truly critical for safe flood operations.

For high wind events, this should include:

• How long crest access can be lost due to spray and wave overtopping before it threatens the dam or appurtenant structures.

• Whether warning systems are vulnerable to wind damage or loss of power.

• How evacuation routes might be blocked by debris, flooding, or traffic during and after a major windstorm.

• Whether gate operation is feasible under extreme wind conditions and what backup power, remote operation, and controls are available.

When we model wind wave runup and slope protection, we should also be asking: “If this scenario occurs, what else will the wind be damaging at the same time?” The Kingsley and Okeechobee events both suggest that near breach conditions can develop over hours, not minutes, leaving a narrow but real window for intervention—provided adequate facilities (such as outlet works), and access and communications remain functional.

Wind-Induced Failure Modes

The historic case studies highlighted reinforce that wind generated waves and wind setup can be primary drivers in an embankment dam failure, not just secondary nuisance loads. Where site conditions permit development of even modest wave heights, repeated wave attack on inadequately protected upstream slopes and crests can initiate erosion, and eventually lead to breach, even at normal pool conditions. In risk analyses, this behavior is best captured as its own potential failure mode (PFM), for example, “wave erosion of crest and upstream face”, informed by both historical performance and site specific wave runup estimates. Additionally, wind induced failures can happen during normal pool conditions which may be more frequent than other loading times, such as seismic and hydrologic, proper loading probability is necessary to accurately develop wind-induced PFMs.

In many regions, strong wind events tend to occur most frequently from a limited range of directions rather than uniformly from all bearings. Where a dam is oriented perpendicular to the prevailing high-wind direction, and the reservoir provides a long effective fetch in that direction, wind-generated wave heights and runup can be significantly increased. In these settings, the likelihood of a wind-related potential failure mode may be elevated, particularly during normal or intermediate pool conditions. Evaluating wind direction relative to reservoir geometry is therefore an important screening step in wind-related failure mode identification.

For risk practitioners, this means wind action on embankments should be screened as a viable failure mode wherever fetch is non trivial, upstream slopes may be inadequately armored or vegetated, or historical accounts indicate wave damage. Evaluations should consider combinations of pool levels with extreme but plausible wind events, associated wave runup and setup, and the resistance of existing slope protection. Where risk estimates are non negligible, owners have several levers available: upgrading riprap or other armoring, improving crest and upstream slope geometry, refining freeboard criteria, and ensuring that wind driven damage states are represented in surveillance and monitoring triggers, and Emergency Action Plans. As was done by Reclamation at Lake Lily Dam, treating wind wave attack as a distinct, credible failure mode encourages more complete risk analyses and paints a more complete holistic picture of a facility’s risk.

Summary of Key Lessons

These cases and the current body of industry guidance (some of which has been referenced herein) suggest several practical lessons for dam safety practitioners:

- For embankment dams, wind generated waves and setup should be considered explicitly in assessing the appropriate freeboard and in sizing slope protection, using site specific wind and reservoir data.

- Riprap and bedding, or alternative slope protection systems must be designed and detailed for the range of expected wave conditions, including the most exposed elevation band. Under designed or poorly detailed protection can allow rapid breach initiation when waves remove armor and expose erodible embankment materials. Normal or intermediate pools subjected to maximum winds can be more critical than peak IDF stages exposed to somewhat lower winds. FEMA’s freeboard guidance and USACE freeboard criteria explicitly encourage this combined load approach.

- Maintain a stockpile of riprap near the dam for intervention and repair when a wind-induced incident occurs.

- Where reservoir fetch is sufficient, wave induced forces on gates, bridge decks, and piers should be part of the hydraulic and structural design, using coastal and reservoir wave theory as suggested in EM 1110 2 1603.

- EAPs and warning systems should consider scenarios where access, power, and communication are degraded by high wind events, as was the case at Lake Okeechobee.

- In risk analyses, teams should consider a dam’s vulnerability to wind and the potential for a high-wind event to cause a credible potential failure mode.

References

(1) Baker, M. E. (2014). Dodging a Bullet: Lily Lake Dam and the 2013 Colorado Flood. 2014 ASDSO Annual Conference Proceedings. Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

(6) Miami–South Florida Weather Forecast Office. (N.D). Memorial Web Page for the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane. Miami–South Florida Weather Forecast Office. National Weather Service.

This Lesson Learned was Peer Reviewed by Tim Gokie, P.E. (Dam Safety Division; Nebraska Dept. of Water, Energy, and Environment Dam Safety Division) and Mark Baker, P.E. (DamCrest Consulting).

Kingsley Dam (Nebraska, 1972)

Additional Case Studies (Not Yet Developed)

- Lily Lake Dam (1951)

- Lake Okeechobee (1926, 1928)

Design Standards No. 13: Embankment Dams - Chapter 17

General Design and Construction Considerations for Earth and Rock-Fill Dams, EM 1110-2-2300

Riprap for Slope Protection Against Wave Action (TR-210-69)

Selecting and Accommodating Inflow Design Floods for Dams

Design Standards No. 13: Embankment Dams - Chapter 7