Abu Mansour & Al-Bilad Dams (Libya, 2023)

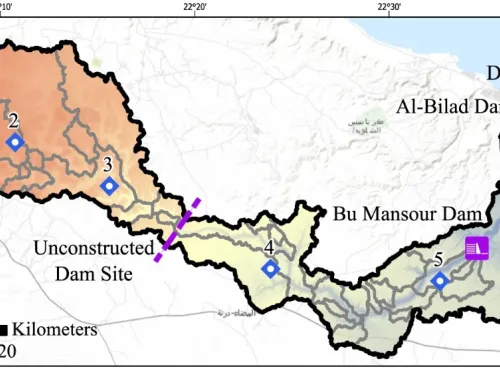

Derna, Libya is defined by its setting on the Mediterranean Sea. It has a robust fishing industry, a renowned seafood scene, thriving forests, and – in a largely arid nation – an unusually moist climate. The city, population 100,000 as of 2023, lies atop an alluvial fan at the mouth of the Wadi Derna, wadi being Arabic for a riverbed. Like most wadis, the Wadi Derna is typically dry. However, this changes abruptly during the region’s infrequent but torrential precipitation events. As a result, Derna has always been prone to flash flooding. Particularly severe floods struck the city in 1941 (sweeping away Nazi tanks), 1956, 1959, and 1968, highlighting the need for effective flood control. Accordingly, after Col. Muammar Qaddafi came to power in Libya in 1969, his government hired a Yugoslavian design and contracting firm to engineer and construct dams in the Wadi Derna valley. From 1973 to 1977, the firm built two earthen dams with compacted clay cores and rockfill faces. The Al-Bilad Dam, about 165 feet above sea level and just within Derna’s city limits, stood 80 feet high and had a storage capacity of 1,200 acre-feet. The Abu Mansour Dam, situated about 550 feet above sea level and 8.5 miles upriver (south) of the Al-Bilad Dam, stood 140 feet tall and had a storage capacity of 18,200 acre-feet. Collectively, the dams stored runoff and inflow from an area of about 215 square miles, most of which lay upstream of the Abu Mansour Dam [3, 5, 8, 12].

Decades of weathering and flash floods compromised the integrity of the Al-Bilad and Abu Mansour Dams. Reports of damage to the structures first emerged following severe floods in 1986. By the late 1990s, problems at the Wadi Derna dams grew so severe that the Qaddafi government became alarmed. When cracks were observed in the structures’ bases in 1998, the government hired Italian civil engineers to assess the dams and recommend repairs. The Italian study confirmed the damage at the dams and provided guidance on how to properly rehabilitate them. The engineers also recommended constructing a third dam in the Wadi Derna valley upstream of both extant structures to help them handle floods more severe than those considered by the Yugoslavian designers. The Qaddafi government hired a contractor in 2007 to carry out the recommendations of the Italian engineers, but work did not begin until late 2010. Unfortunately for the Wadi Derna dams, the Arab Spring convulsed Libya the next year, and Col. Qaddafi was overthrown and killed. The nation was consumed by a brutal civil war for much of the ensuing decade. While Libya’s political situation stabilized in the late 2010s, the repairs and third dam recommended in the Italian study never materialized [2, 3, 8].

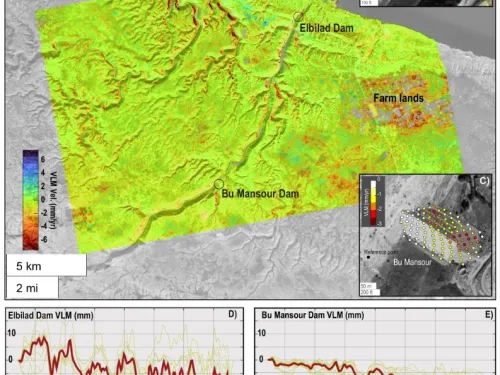

By the early 2020s, the Al-Bilad and Abu Mansour Dams were increasingly at risk of failure. They had not been maintained for decades – since 2002 per some local accounts, since 1983 by others. Vegetation was seen to be growing on the Abu Mansour Dam, a sign of internal leaks. In addition, both dams had been damaged during Libya’s civil war. Furthermore, their hazard classifications had changed as Derna’s population had swelled. The structures had rendered the city’s frequent floods a distant memory, giving new residents a false sense of security, and new development often extended into the historical flood plain. Making matters worse, the population boom also strained aquifers in the Wadi Derna region, which almost certainly impacted the dams. Satellite images from 2016 to 2023 showed 0.4 inches of subsidence or settlement at the Al-Bilad Dam and 0.6 inches at the Abu Mansour Dam during that time. Finally, climate change was steadily altering the Derna region’s ordinarily temperate weather patterns, curtailing the growth of vegetation in the Wadi Derna valley and increasing the runoff the dams had to handle. Experts and locals, including a prominent Libyan civil engineer, warned for years of the impending danger from the dams’ lingering problems, but these concerns went unheeded [2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9].

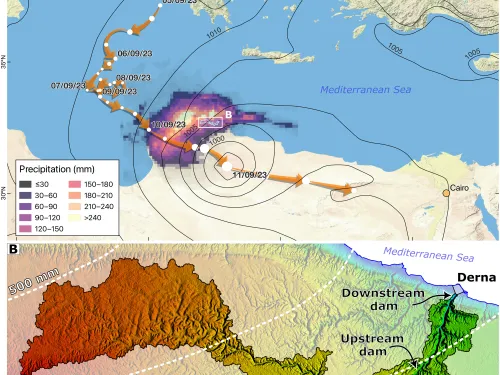

In early September 2023, Storm Daniel, a Mediterranean cyclone (commonly termed a “medicane”), barreled south from Greece toward Derna. Its barometric pressures were below those of most medicanes, and it arrived much earlier. Storm Daniel was further intensified by the unusually warm summer, which had heated the waters of the Mediterranean Sea. Another factor that strengthened the medicane was anthropogenic climate change, which one study concluded had made it up to 50 times likelier and 50% worse. Before Storm Daniel neared Derna on Sunday, September 10th, the weather there had been rather dry, and the reservoir behind the Abu Mansour Dam was empty as of 6:30 PM. When the medicane rolled in later that evening, though, it dumped roughly 14 inches of rain over the Wadi Derna watershed. This rainfall corresponded to a storm of less than 0.1% annual probability, which is within the typical range of what a high hazard dam is designed to withstand. However, the ensuing runoff was seven times greater than the discharge capacities of the Al-Bilad and Abu Mansour Dams, an indicator that their spillways were woefully undersized [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 10].

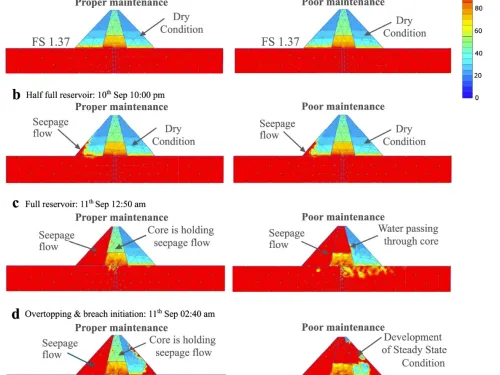

The problems worsened as September 10th slipped into the 11th. The Al-Bilad and Abu Mansour Dams would never have had high factors of safety for slope stability during a medicane as intense as Storm Daniel. Post-flood geotechnical modeling found that the Abu Mansour Dam as first built would have had an FS of 1.11 in the face of such a storm. Sadly, decades of insufficient maintenance had lowered these FS values even further, as cracks formed in the structures that led to high rates of seepage and piping and almost surely accelerated their failure. Studies suggested that such cracks lowered the FS of Abu Mansour Dam from 1.11 to 1.07 – not a dramatic decrease, but most likely enough to push the structure from marginal stability toward imminent failure [5].

Eventually, the dams overtopped by several feet and failed. Eyewitness accounts indicate that the Al-Bilad Dam breached first, undergoing about 10 feet of overtopping before failing in the early hours of September 11th. The resulting flood wave inundated the lower floors of buildings throughout Derna and forced residents to high ground. Just a few hours later, at around 2:40 AM, the Abu Mansour Dam also breached after experiencing about 6.5 feet of overtopping. The torrent of water released in this later, much larger failure created an even higher flood wave through Derna. All in all, the breaches let loose about 24,300 acre-feet of water. Thousands of Derna residents who had believed themselves to be on safe, high enough ground discovered to their horror that they were not [5, 9, 12].

Storm Daniel’s intense rains would certainly have hit the Wadi Derna valley hard even had the Al-Bilad and Abu Mansour Dams held, but their failures worsened the catastrophe by an order of magnitude. Researchers estimated via hydraulic modeling that the dam breaches deepened flooding across most of Derna by 6 to 20 feet compared to a no-dam scenario. Robust operations and maintenance procedures might not have saved the dams during Storm Daniel but could still have provided more time for evacuations. However, this added time might not have helped, since the region’s flood alert systems were functioning poorly. Derna residents reported that they not only received too little warning to evacuate before the breaches but that these notices were often wildly inaccurate – for instance, not advising people in the most flood-prone areas to seek higher ground. Thus, the dam failures turned an already bad disaster into a truly horrific one [1, 3, 4, 5].

The precise tally of victims from the Al-Bilad and Abu Mansour Dam breaches remains unknown. While 4,000 are confirmed to have perished, the death toll is likely closer to 12,000 once those still listed as missing are also considered. The disaster left 9 million tons of debris strewn across Derna, and the government’s ongoing cleanup and reconstruction of the city is currently projected to cost $2.1B. Some have characterized the breach of the Wadi Derna dams as an “act of God” or a “natural disaster.” However, the double breach reminds dam engineers of their solemn obligations to properly assess risks from storms at dams and to design appropriately for these hazards [2, 6, 11, 12].

References:

(3) Mauney, L. (2023). Derna, Libya Dam Failures: September 11, 2023. [PowerPoint slides]. 2023 ASDSO Annual Conference. Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

(7) Petley, D. (2023, September 14). Further information about the Wadi Derna dams. Eos.

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by William Johnstone, Ph.D, P.Eng. (Spatial Vision Group) and Paul Risher, P.E. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers).

Lessons Learned

Dam incidents and failures can fundamentally be attributed to human factors.

Learn more

Dam owners, engineers and regulators need to address public safety at dams.

Learn more

Dams should be thoroughly assessed for risk using a periodic risk review process including a site inspection, review of original design/construction/performance, and analysis of potential failure modes and consequences of failure.

Learn more

Dozens of dams can fail or be in danger of failing during a single event (i.e. swarming failures). Dam owners and regulators need to prepare for these types of events.

Learn more

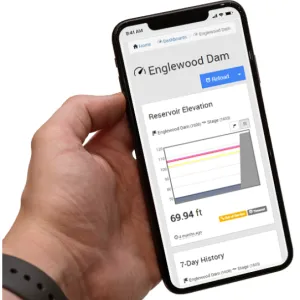

Early Warning Systems can provide real-time information on the health of a dam, conditions during incidents, and advanced warning to evacuate ahead of dam failure flooding.

Learn more

Extreme floods do occur.

Learn more

Regular operation, maintenance, and inspection of dams is important to the early detection and prevention of dam failure.

Learn more

The hazard classification of a dam can change over time (hazard creep).

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn moreAdditional Lessons Learned (Not Yet Developed)

- Adequate spillway design is essential to ensure the proper functioning of a dam.

Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety

Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety - Emergency Action Planning for Dams

Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety - Hazard Potential Classification System for Dams

Federal Guidelines for Inundation Mapping of Flood Risks Associated with Dam Incidents and Failures

Summary of Existing Guidelines for Hydrologic Safety of Dams

Technical Manual: Overtopping Protection for Dams

Evaluation and Monitoring of Seepage and Internal Erosion