Machhu Dam II (Gujarat, India, 1979)

On August 10, 1979, monsoon storms poured over Gujarat, India. Monsoon rainstorms were not uncommon in this part of India, but as the storm increased it was clear this was larger than the usual storm. Flow began to increase down the Machhu river, first hitting Machhu Dam I and then turning downstream to Machhu Dam II. As the storm intensified, operators at the Machhu Dam II began to open gates to keep the dam from rising above maximum levels. By 1:30 AM all the gates were opened fully except for three gates that were not properly functioning. Despite the nonoperational gates the dam was passing 196,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), very close to its full capacity of 200,000 cfs. It wasn’t enough, and the water continued to rise. It was early afternoon on August 11, 1979 when water overtopped the earthen embankments on both sides of the masonry spillway leading to the failure of Machhu Dam II.

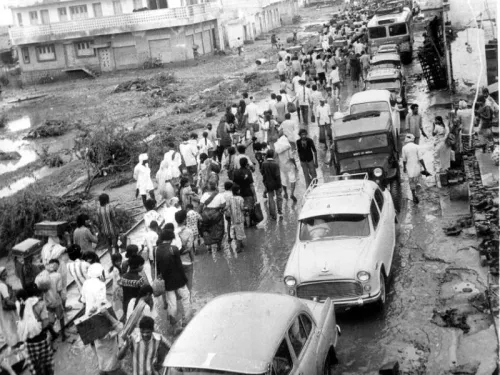

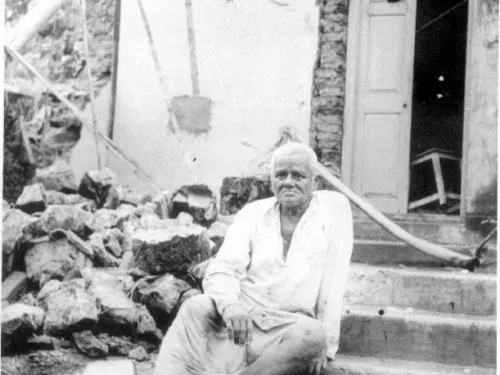

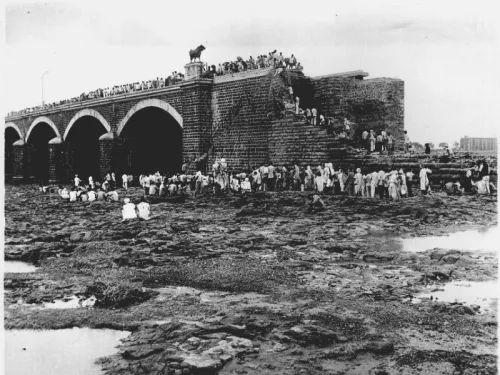

A warning had been sent out through the All-India Radio broadcast around noon instructing people to move to higher ground because of potential issues at the dam. However, communication from the dam site had failed and no official warning of the dam failure was issued. Approximately 90,000 acre-feet of water joined the already heavy flow from the river and rushed into the small town of Lilapar completely inundating all the buildings in the town. Thankfully, the people of Lilapar had largely heeded the early warning.

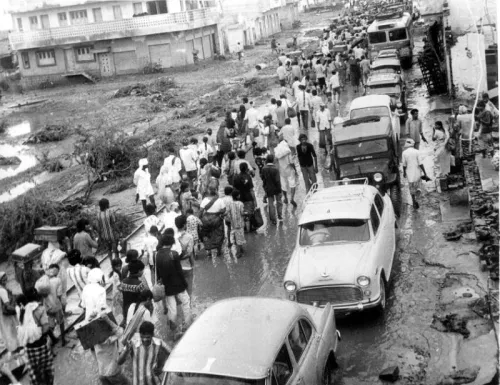

On the other hand, few in the much larger town of Morbi gave heed to the warning. Flooding during the monsoon season was not uncommon and many people assumed this flood would not be much different than past floods and failed to grasp the magnitude of the disaster. Because of this, many refused to evacuate, or did not evacuate to high enough ground. In Vajepar, an agricultural community on Morbi’s outskirts, people evacuated to the local temple because it had been out of the inundation area of the last large flood. Water rushed into the temple making escape impossible and killing over 100 people. The flood wave then pushed on to Morbi where it destroyed buildings, killed livestock and took lives. No one knows for sure how many lives were lost, but estimates range from 1,800 to as high as 25,000. Part of the reason the number varies so much is that large mass graves were burned to keep diseases from spreading before proper records or any identification could be completed.

An official government inquiry was assembled to determine the cause of the failure. The government itself quickly put forth that the flood was beyond anything that the state of the practice would have required and that the flood that was over three times the spillway capacity was not foreseeable. The chief engineer refused to testify, and the government disbanded the inquiry before they completed any report.

There was a report completed on the failure of the dam by Dr. Y. K. Murthy in 1985. While his estimate of the peak inflow at 460,000 cfs is less than the government estimates, which range between 630,000 and 936,000 cfs, he agreed that overtopping of the dam that only had a spillway capacity of 200,000 cfs was inevitable. He also agreed that the spillway design capacity of 200,000 cfs was in accordance with the state of the practice for that period of time.

Machhu Dam II was ultimately rebuilt with a spillway capacity of 872,000 cfs and was completed in 1989. It is still in operation today.

References:

(2) Patel, Z. The Machhu Dam Disaster of 1979 in Gujarat.

(4) 1979 Machchhu dam failure. Wikipedia. (5) Morbi Machhu Dam Failure. Indian News Review.

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by Lee Wooten, P.E., GEI Consultants, Inc.

Lessons Learned

All dams need an operable means of drawing down the reservoir.

Learn more

Emergency Action Plans can save lives and must be updated, understood, and practiced regularly to be effective.

Learn more

Extreme floods do occur.

Learn more

High and significant hazard dams should be designed to pass an appropriate design flood. Dams constructed prior to the availability of extreme rainfall data should be assessed to make sure they have adequate spillway capacity.

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn moreAdditional Lessons Learned (Not Yet Developed)

- Extreme floods do occur.

- Many years of successful dam performance does not guarantee future successful performance.

- Gates and other mechanical systems at dams need to be inspected and maintained.

- Operators for primary spillway gates must be reliable, must have back-up systems, and must be tested regularly to ensure reliability.

- Communication and operational coordination between dams on the same river system are critical during floods.

A Guide to Public Alerts and Warnings for Dam and Levee Emergencies

Emergency Action Planning for State Regulated High-Hazard Potential Dams - Findings, Recommendations, and Strategies

Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety

Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety - Emergency Action Planning for Dams

No One Had a Tongue to Speak

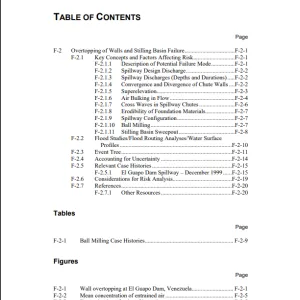

Selecting and Accommodating Inflow Design Floods for Dams

Summary of Existing Guidelines for Hydrologic Safety of Dams