Description & Background

Castlewood Canyon Dam was constructed in 1890 across Cherry Creek, 40 miles southeast of Denver, Colorado. The masonry and rock-fill structure, built from local materials, was around 600 feet long with a height of 70 feet measured from the reservoir floor, 8 feet wide at the crest, and 50 feet wide at the base. The dam was regulated by an outlet structure with eight 12-inch inlet pipes and one 26-inch outlet pipe. The dam had a 100-foot long by 4-foot deep notched uncontrolled spillway at the center of the crest and a 40-foot wide masonry-lined bypass spillway near the left abutment. The 5,300 acre-feet of storage was used for irrigating fertile Douglas County farmland, dotted with dairy farms, potato fields and orchards.

The dam was controversial from the beginning. Just after construction, Castlewood Dam showed signs of settlement, with cracks and seepage visible on the face of the dam. Safety was questioned by downstream citizens and a committee of engineers determined that improvements to the dam were necessary. All the while, Denver Water Storage Company, owner of the dam, and the dam’s designers argued that the dam was safe. In 1897, a section of the dam washed out prompting multiple repairs. Following the repairs, leakage remained visible, but to a lesser degree. The back and forth continued between the citizens and owner, prompting the chief engineer to issue a foretelling letter.

“The Castlewood Dam will never, in the life of any person now living, or in generations to come break to any extent that will do any great damage either to itself or others from the volume of water impounded, and never in all time to the city of Denver.” – A.M. Welles, Chief Engineer

The 175 square mile Castlewood Canyon drainage basin, located in the upper portion of the greater Cherry Creek Basin, consisted of mostly rural farmland and ranged in elevation from 6,500 to 7,500 feet. In late June and early August of 1933, locals experienced a continued wet period. Some estimated the wet spell to be three days, others as long as a week. On the afternoon of August 2nd, between 4 to 9 inches (estimates vary) of rain fell in approximately three hours from a localized storm event.

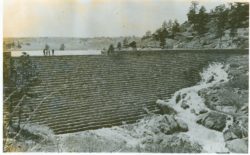

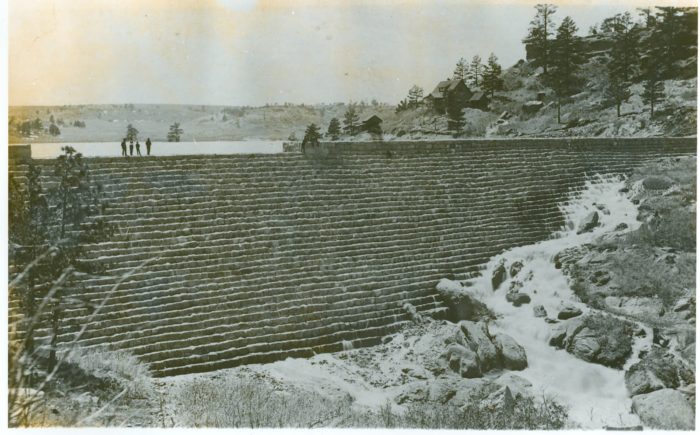

Men standing on spillway watch seep from face of Castlewood Dam, near the left abutment. (Photo source: Colorado Historical Society)

Coloradans know all too well the potential for flooding during summer thunderstorms. In fact, July and August have seen some of the most well-known events in State history – Cub Creek (July 1896), Buckhorn Dam Failure (August 1951), Big Thompson Canyon Flood (July 1976), Fort Collins Flood (July 1997), and most recently, the Manitou Springs flooding from Waldo Canyon (August 2013). As history has shown, August 1933 was no exception.

At around 11:15 p.m. on the evening of August 2nd 1933, the reservoir level behind Castlewood was about 6 feet below the spillway crest. By midnight, the water level had risen to the crest of the dam, and only 15 minutes later, water was overtopping the dam crest by approximately one foot. It is estimated that approximately one hour later, around 1:20 a.m. on August 3rd, 1933, Castlewood Canyon dam was breached, sending a wave of water down the canyon towards Denver. Peak discharge immediately downstream was later estimated at 126,000 cubic feet per second (cfs).

The flood wave first passed through rural farmland and washed out county bridges. It reached the outskirts of Denver between 5 and 6 a.m. There were two flood waves reported, an initial wave probably caused by water spilling from and overtopping the dam, and then a larger, more destructive wave approaching 15 feet high. By 7 a.m., six hours after the breach, the flood wave made it to downtown Denver, flooding businesses and homes with an estimated discharge of 15,000 cfs.

A forensic investigation, published in the Association of State Dam Safety Officials Journal of Dam Safety (2013), would later use modern quantitative evaluation methods to gain a better understanding of the failure mechanisms. The report noted that the dam was overtopped over the entire length of the crest during the flood event and that there was no significant evidence to support any failure mode other than overtopping and scour of either the downstream masonry of the dam or materials near the toe.

“During the 1933 thunderstorm the reservoir rapidly filled until water flowed over the central spillway and eventually overtopped the remainder of the dam by a little over a foot. Prior to the build-up of tailwater, erosion likely initiated at the toe of the central spillway section. The masonry apron in this location was washed away and deep erosion of the underlying mudstone quickly ensued. At the same time, scour may have begun along the groins due to the overtopping flow. Support for the mortared downstream masonry facing was lost, and it collapsed into the erosion hole. The interior rubble masonry progressively collapsed and eroded. This likely created a hole under the dam that caused the reservoir to drop rapidly... Eventually, the mortared upstream masonry face was exposed over a large enough area that it could no longer support the reservoir load and collapsed.”

Hugh Pain, the dam tender, lived at the site with his wife and heard the roar of water going over the dam. He was the only known witness to the failure event. After first unsuccessfully trying to phone, Paine drove 12 miles to call the Denver Police and the local telephone operator. This would prove to be a key factor to saving lives during the flood. The warning was sent out over telephone line and radio. The telephone operator on duty that night was Nettie Driskill. Later regarded as a hero, Nettie called residents along Cherry Creek, issuing a detailed and concise warning, telling them to “hurry to higher ground.” It is estimated that around 5,000 people fled the lowlands in time to avoid the deadly rush of water.

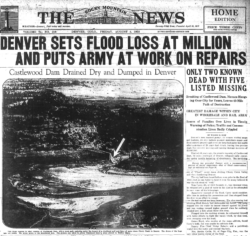

Ultimately, the failure of Castlewood Canyon Dam caused two fatalities and $1M ($20M in 2018) worth of damage to crops property and animals, yet could have been substantially worse. Because the immediate downstream area was rural farmland, major residential structures were left unharmed. The local community had knowledge of the history of the dam and a general understanding of the potential consequences if it were to fail. Before the times of Emergency Action Planning, residents probably imagined and prepared for what they would do in case of disaster. They felt Castlewood Dam was unsafe and this belief was magnified by media coverage in the preceding decades.

Residents were aware of flood risk due to previous flood events and knew better than to build within the floodplains of Cherry Creek. Denver was first settled in the 1850’s and thereafter experienced a series of major floods. In 1864, Denver saw flooding along Cherry Creek that killed nineteen people. Flooding caused major damage again in 1878, 1885, and 1912. Locals warned settlers not to build in the floodplain, and although it took several fatalities and significant economic damage before learning, settlers eventually learned it was not worth the risk to build there.

Today, Cherry Creek is a popular greenway, taking cyclists and runners from downtown Denver to Cherry Creek Dam, a large Army Corps of Engineers structure that provides flood control. The broken remains of Castlewood Canyon Dam are still in place, located amongst hiking trails in Castlewood Canyon State Park. The crumbling remnants of the dam provide a valuable educational opportunity for visitors, reminding us of both the benefits and risks we must navigate when living with our Nation’s dams.

References:

(5) Engineering News-Record. (1933). Castlewood Dam Failure Floods Denver. Engineering News-Record.

(6) Colorado History Museum. (2013). Castlewood Canyon flood photograph album. Denver, CO: Colorado History Museum.

(7) Denver Public Library. (2018). Digital Collections. Denver, CO: Denver Public Library.

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by Douglas L. Johnson, P.E., Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Summary

Photos

- One of the only known construction photos. Looking toward the right abutment. Stiff-legged derricks used to move large stone into position. (Photo source: Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, 1890)

- Men standing on spillway watch seep from face of Castlewood Dam, near the left abutment. (Photo source: Colorado Historical Society)

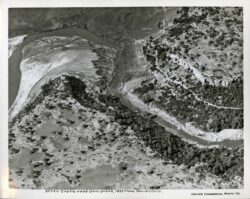

- Aerial view of Cherry Creek and Castlewood Canyon Dam. Ruins of the broken dam are strewn in the riverbed. (Denver Public Library Special Collections, X-24013)

- Newspaper clipping: Denver sets flood loss at million and puts army at work on repairs. (Photo source: the Rocky Mountain News, August 4, 1933)

- Flood damage in Denver from Castlewood Dam break. (Photo source: Denver Public Library Special Collections, X-29285)

- Today Cherry Creek Dam provides flood control along Cherry Creek in Denver CO. (Photo source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District)

- The remnants of the broken dam remain in place, located in Castlewood Canyon State Park. Photo was taken in 2012. (Photo source: Lee Mauney)

Videos

- Universal Newspaper Newsreel video clip

- Great Dam Bursts, Denver, Col. (1933)

- Castlewood Canyon State Park: Original History

- Castlewood Canyon, CO in 2.7K

- Cherry Creek Flood, Denver Public Library, 1933 (full, unedited)

- Animation of overtopping failure developed by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

Lessons Learned

Dam failure sites offer an important opportunity for education and memorialization.

Early Warning Systems can provide real-time information on the health of a dam, conditions during incidents, and advanced warning to evacuate ahead of dam failure flooding.

Floods can occur due to unusual or changing hydrologic conditions.

High and significant hazard dams should be designed to pass an appropriate design flood. Dams constructed prior to the availability of extreme rainfall data should be assessed to make sure they have adequate spillway capacity.

Regular operation, maintenance, and inspection of dams is important to the early detection and prevention of dam failure.

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Additional Lessons Learned (Not Yet Developed)

- External independent peer review of designs and decisions is an effective means of providing quality assurance with design oversights and deficiencies.

- Dam inspections should be performed by qualified Dam Inspectors.

- Floodplain management can reduce risk by minimizing population at risk below dams.

- Having a knowledgeable and engaged public can help with warning and evacuations during a flood event.

- A clear, concise warning message with specific details are more likely to be heeded during an emergency situation.

Other Resources

Reassessment of the Castlewood Dam Failure

Author: C. Leibli, G. Scott, & P. Schaffner

Army Corps of Engineers, Risk Management Center

Why Wasn’t Castlewood Worth a Dam?

Author: C. Leibli, G. Scott, G. Annandale, P. Shaffner, & J. Higgins

The Journal of Dam Safety (ASDSO)

The Night the Dam Gave Way: A Diary of Personal Accounts

Author: Castlewood Canyon State Park

Federal Guidelines for Inundation Mapping of Flood Risks Associated with Dam Incidents and Failures

Author: Federal Emergency Management Agency

Technical Manual: Overtopping Protection for Dams

Author: Federal Emergency Management Agency

Summary of Existing Guidelines for Hydrologic Safety of Dams

Author: Federal Emergency Management Agency

Selecting and Accommodating Inflow Design Floods for Dams

Author: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

Evaluation and Monitoring of Seepage and Internal Erosion

Author: Interagency Committee on Dam Safety (ICODS)

80th Anniversary of the Castlewood Dam Failure

Author: L. Mauney

ASDSO Decade Dam Failure Series Presentation