South Fork Dam (Pennsylvania, 1889)

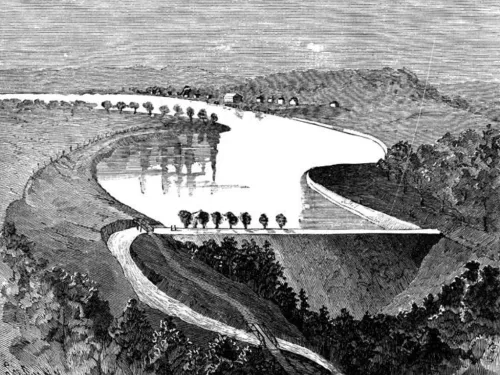

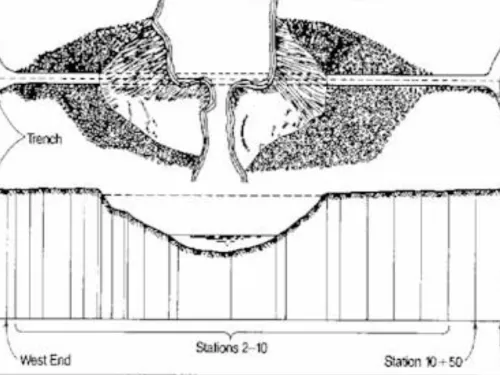

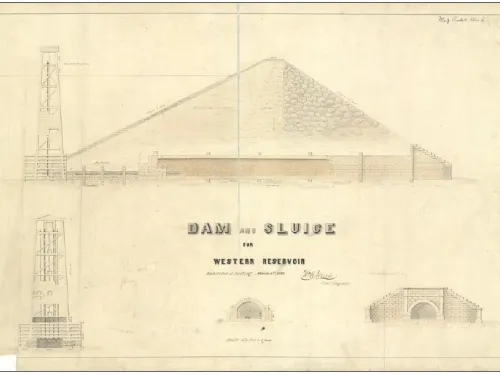

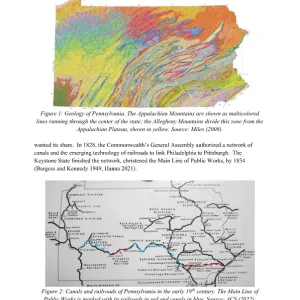

Civil engineers in Pennsylvania designed and supervised the building of a cross-state network of railroads and canals linking Philadelphia to Pittsburgh during the early 19th century. As part of this system, a reservoir and embankment dam were built in southwestern Pennsylvania to supply water to a canal terminal in the village of Johnstown. The body of water, named the Western Reservoir, and its dam were 14 miles away from the canal terminal via the Little Conemaugh River and 400 feet in elevation above it. The civil engineering and construction of the Western Reservoir and dam met the contemporary standard of care, but improved railroads soon rendered them obsolete, and they were neglected. The dam partially failed in 1862, emptying the reservoir, but no fatalities and only minor property damage ensued. The dam remnants were then abandoned and sat exposed for nearly two decades.

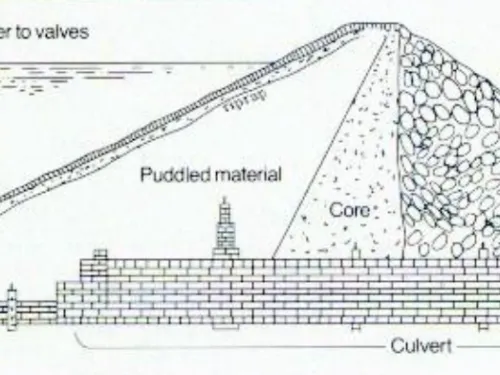

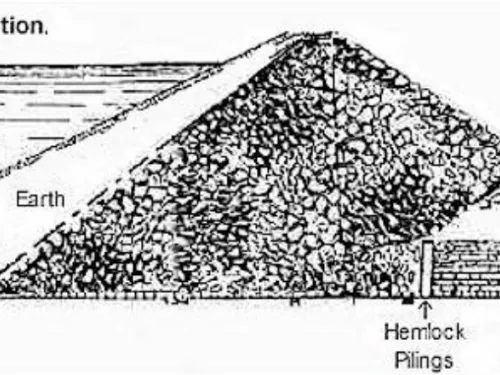

In the late 1870s, Pittsburgh tycoon Benjamin Ruff and some fellow moguls founded the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. The Club purchased the old reservoir site and dam remnants with plans to create an exclusive lakeside resort for their group by reconstructing the dam and reimpounding the reservoir. Ruff supervised the dam reconstruction but had no engineering training of any kind and scarcely involved qualified civil engineers. Thus, he and a local contractor’s crew rebuilt the embankment, now renamed the South Fork Dam, without meeting the contemporary or even original standard of care for constructing dams.

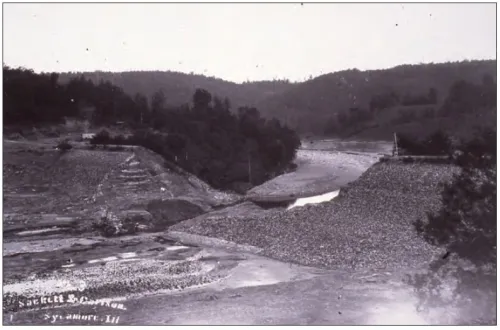

Several qualified engineers expressed concerns about Ruff’s shoddy work; the most notable objections came from the head of Johnstown’s Cambria Iron Company, then a major steel manufacturer in the USA. Yet Ruff curtly dismissed these worries as he rebuilt the South Fork Dam and reimpounded the reservoir, now renamed Lake Conemaugh. The dam had some close calls during the 1880s, but locals and South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club members alike quickly grew numb to fears it would breach. Few seemed aware of deep-seated problems at the dam, such as extensive seepage and a central sag where poorly placed material had been used to backfill the 1862 breach.

“You and your people are in no danger from our enterprise.” (Letter from Benjamin Ruff of South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club to Daniel Morrell of Cambria Iron Company, December 2, 1880, regarding reconstruction of South Fork Dam.) [4]

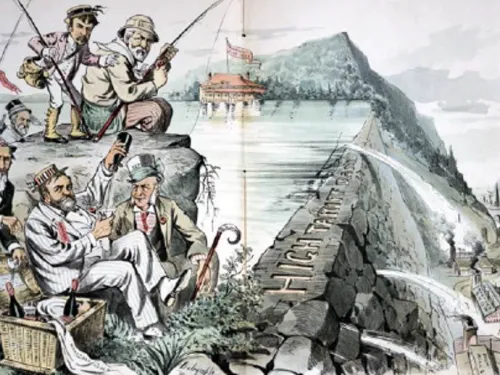

The 1880s at the Club and in Johnstown represented a juxtaposition of two radically different worlds. At Lake Conemaugh, Club members such as captains of industry Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon traveled from Pittsburgh to enjoy angling, marksmanship, sailing, hunting, and picnicking, among other summer pastimes. Many members built sumptuous summer homes for their families along the lake’s shoreline. By contrast, Johnstown – 8 miles from the Club as the crow flies – revolved around the grueling, grimy, and often deadly work of the Cambria Iron Company and the Pennsylvania Railroad. However, most Johnstown citizens felt they were helping their community and nation build a bright future.

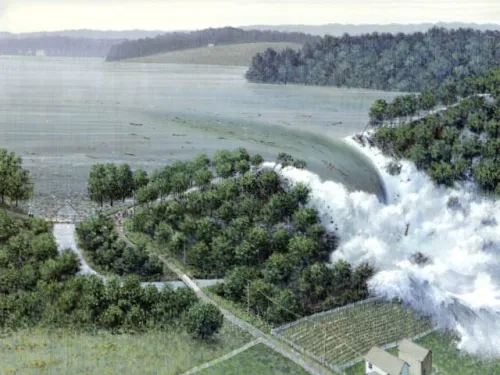

However, that future darkened in late May 1889. A torrential overnight rainstorm on May 30-31, estimated to be a 2 percent annual probability event, dumped 6 to 7 inches in the Lake Conemaugh area. By morning on the 31st, the lake level was rising 9 to 10 inches per hour, and those readying the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club for the summer season knew right away that the South Fork Dam was in trouble. Attempts were made to alert the roughly 30,000 residents of the Little Conemaugh valley to the danger, but most – jaded by the “boy who cried wolf” nature of these rumors – ignored them. Eventually, the lake overtopped the dam and caused an initial breach due to headcut migration. The dam then suffered a final, far more catastrophic breach, most likely due to sliding.

The final breach of Lake Conemaugh sent 16 million tons of water thundering down the Little Conemaugh River valley. The two worlds of the Club and the valley below collided violently as the tsunami-like flood wave devoured everything in its path, including houses, trains, livestock, and – tragically – unsuspecting people. The deluge impacted numerous communities but Johnstown, as the largest of them, gave the disaster its name as the “Johnstown Flood.” The flood’s horrors were compounded when a pile-up of flammable debris in Johnstown ignited into an inferno that burned for days.

The outside world responded almost immediately to word of the disaster. The American and global public gave generously in both money and supplies to the flood relief cause. Soldiers, medical personnel, and volunteers headed to the area to help traumatized survivors clean up their wreckage, rebuild their lives, and bury their dead. The breach ultimately led to roughly 2,500 direct and indirect fatalities, making it the deadliest-ever US dam failure.

“None was afraid to meet God, but we all felt willing to put it off.” (Rev. H.L. Chapman on waiting out the Johnstown Flood of 1889 with friends and family in his attic.) [4]

Journalists soon revealed how poorly the South Fork Dam had been rebuilt. Public outrage over the disaster and calls for justice and reform were widespread, and efforts ranging from lawsuits to an American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) select committee investigation got underway to attempt to hold the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club members to account. However, the tycoons were well-connected, and circumstantial evidence suggests they thumbed the scales of power to protect themselves from the flood’s legal and financial fallout. The moguls effectively compromised politicians, judges and juries, and even the ASCE investigation of the dam breach.

The 135 years since the South Fork Dam breach have witnessed immense changes in both civil engineering practice and the Johnstown area. Civil engineering has grown and matured with the rise of disciplines such as geotechnical and dam engineering, and civil engineers have become subject to licensure laws and ethics codes. Dam safety has been subjected to federal and state regulation, and organizations such as the United States Society on Dams (USSD) and Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) in the US and International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD) around the world have played and continue to play major roles in enhancing these standards. The telling of the Johnstown Flood of 1889 has also evolved. Citizens in the area spent decades after the calamity seeking to move past it, but eventually embraced the disaster as part of their regional heritage. Since the 1960s, many authors have published reliable sources on the historical and technical sides of the Johnstown Flood of 1889, and the tale of the tragedy continues to resonate. As modern Johnstown seeks its post-industrial footing, the area’s flood heritage brings in tourism and boosts the city’s economy. Meanwhile, civil engineers across the US grapple with aging infrastructure – especially dams – and the related problems of inadequate funding and flagging public support.

The Johnstown Flood of 1889 continues to hold important lessons. The event reminds civil engineers, especially dam and geotechnical engineers, that they must overcome challenging project conditions mainly with technical expertise, not business or managerial judgment. Doing so requires meeting the contemporary standard of care in civil engineering and constantly remembering that failed work by the profession can have awful human impacts. Moreover, the dam breach and flood illustrate for people in all careers that historical events, like current ones, were never preordained and that both legal sanctions and constraints of conscience are necessary to guard against human self-interest. A visit to the South Fork Dam remnants, which are now part of the Johnstown Flood National Memorial, vividly underscores all these lessons.

Learn More

The author has also prepared a more comprehensive summary of this case study which can be accessed from the "Other Resources" tab or downloaded in PDF format here: Reexamining the Dam and Geotechnical Engineering Aspects of the 1889 South Fork Dam Breach and Johnstown Flood

References

(1) Coleman, N.M. (2019). Johnstown’s flood of 1889: Power over truth and the science behind the disaster. Springer.

(4) McCullough, D. (1968). The Johnstown Flood. Simon and Schuster.

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by William Bingham, P.E. (Gannett Fleming – retired), Neil Coleman, P.G. (University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown – retired), Christopher Coughenour, Ph.D. (University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown), Carrie Davis Todd, Ph.D. (Baldwin Wallace University), Brian Greene, Ph.D., P.G. (Gannett Fleming – retired), Dina Hunt, P.E. (Gannett Fleming), and Andrew Rose, Ph.D., P.E. (University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown).

Lessons Learned

All dams need an operable means of drawing down the reservoir.

Learn more

Dam failure sites offer an important opportunity for education and memorialization.

Learn more

Dam incidents and failures can fundamentally be attributed to human factors.

Learn more

Earth and rockfill embankment dams must be stable under the full range of anticipated loading conditions.

Learn more

High and significant hazard dams should be designed to pass an appropriate design flood. Dams constructed prior to the availability of extreme rainfall data should be assessed to make sure they have adequate spillway capacity.

Learn more

Regular operation, maintenance, and inspection of dams is important to the early detection and prevention of dam failure.

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn moreAdditional Lessons Learned (Not Yet Developed)

- Dam design, construction, and operation and maintenance must be done under the close supervision of trained and licensed civil engineers specializing in dam engineering.

A History of Johnstown and the Great Flood of 1889

Dam Breach Hydrology of the Johnstown Flood of 1889 - Challenging the Findings of the 1891 Investigation Report

Historic Structure Report, The South Fork Dam Historical Data, Johnstown Flood National Memorial, Pennsylvania, Package No. 124

In the Shadow of the Dam

Johnstown Flood Debate Renewed: UPJ Geologists' Report Questions Findings of Early Investigation into Cause of 1889 Dam Failure

Major Historical Dam Failures with Modes of Failure

Overtopping Failure - Best Practices in Dam and Levee Safety Risk Analysis

Physical Modeling of Overtopping Erosion and Breach Formation of Cohesive Embankments

Reexamining the Dam and Geotechnical Engineering Aspects of the 1889 South Fork Dam Breach and Johnstown Flood

Revisiting the Timing and Events Leading to and Causing the Johnstown Flood of 1889

The Influence of Dam Failures on Dam Safety Laws in Pennsylvania

Additional Resources not Available for Download

- VandenBerge, D., Duncan, J., & Brandon, T. (2011). Lessons Learned from Dam Failures. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.