Dam failure sites offer an important opportunity for education and memorialization.

Dam failure sites are important opportunities to honor victims, educate dam safety professionals, and raise awareness of both the risk posed by dams, as well as the numerous benefits dams provide, while highlighting the need for continued public funding of the Nation’s infrastructure. Challenges may exist related to funding, safety, and legal concerns, but a range of options are available to commemorate locations where significant dams have failed, and many successful examples can be toured across the United States. At the same time, there are seminal dam failures sites that have been forgotten or are difficult to locate and visit. When a dam fails, there is often pressure to remove the remains or rebuild the dam in order to expeditiously move beyond the incident. However, in certain cases, memorializing a failed dam is an opportunity worth pursuing.

Potential Benefits of Commemorating Dam Failure Sites

Honors Victims and Recognizes Heroes

An important benefit of commemorating dam failures is the opportunity to memorialize victims impacted by the failure, by both remembering those who didn’t survive, and telling the often heroic stories of those who did. In the hurry to clean up debris and wreckage at and downstream of a dam, the consequences of the event and victims impacted by dam failures should not be forgotten. In fact, recognizing the loss can be an essential part of the recovery effort. In addition, memorials can pay tribute to those who heroically saved lives and property during and following a dam failure (Photo 1).

Elevates Public Awareness

Dams are a critical piece of the infrastructure in the United States, providing a range of economic, environmental, and social benefits, including hydroelectric power, river navigation, water supply, wildlife habitat, waste management, flood control, and recreation [3]. Dams have a powerful presence, both related to benefits and risk, which is frequently overlooked until a significant failure has occurred [4].

Some of the strongest state dam safety programs in the U.S. were established in response to devastating dam failures like St. Francis Dam. A series of dam failures during the 1970’s, including Buffalo Creek, Teton Dam and Kelly Barnes Dam, helped spur key Federal legislation related to national dam safety standards. Improved dam safety programs have helped in reducing major dam failures, but much work remains. From 2005 to 2013, state dam safety programs reported 173 dam failures in the U.S. [5].

In order to keep additional dam failures from occurring, the country must address the continued deterioration of this important national infrastructure. A 2019 report estimates $65 billion will be required to rehabilitate all federal and non-federal dams across the U.S. [3]. Much of these improvements would be funded by taxpayer dollars, necessitating an understanding and consensus between politicians willing to sponsor legislation and a population willing to foot the bill. Dam failure sites highlight the consequences of what can happen if dam deficiencies are not addressed.

In addition, there are more tangible benefits to the public being aware of our Nation’s dam inventory. Historic flooding and dam failure case studies suggest that population-at-risk (PAR) can be more likely to heed warnings if they are aware of the potential risk posed by a flood event or dam failure prior to being asked to evacuate. For example, in 1933 when residents living below Castlewood Canyon Dam in Colorado were told the dam was failing, they reacted immediately because they were well aware of the dangers associated with the dam. Memories of the 1976 Big Thompson Canyon flood likely contributed to fewer fatalities in Colorado during both the Lawn Lake Dam failure [6] and a more recent major flood event that occurred in that same canyon in 2013 [7].

Educates Dam Safety Professionals

Failed dam sites offer unique and interactive educational tours for career dam safety professionals, engineering students, and potential or current STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) majors. Henry Petroski, acclaimed engineer and historian, writes that the concept of failure is central to understanding engineering, specifically because “engineering design has as its first and foremost objective the obviation of failure”, and that incidents and failures are “unplanned experiments that can teach on how to make the next design better.” These lessons, he suggests, should be a permanent part of the engineering curriculum [8].

When tourists visit the Great Falls of the Potomac River, just miles from the Nation’s Capital in Washington D.C., next to a series of steep, jagged rocks, with cascading rapids over several twenty foot waterfalls, they see a signpost displaying recorded historic high water marks at that location (Photo 3). Visitors can visualize the record flows inundating the park, and these historic levels serve as data points for hydrologists estimating future peak flows along the Potomac [9]. In a similar way, dam failure sites can be full-scale laboratories for dam safety professionals, and investigations years or even decades after a failure can lead to important insights (Photo 4). In 2012, engineers reanalyzed failure modes at Castlewood Canyon Dam, nearly 80 years after the dam breached in 1933, by conducting on-site geologic investigations of exposed erosional cuts and a construction material characterization of embankment remains (Photo 5), leading to a scour analysis that furthered understanding of the case study [10]. The failure modes associated with St. Francis Dam were not fully understood until continued site investigations decades after its failure [11]. It is unknown what technologies may emerge to better investigate dam failures, but having failed dams in place may provide chances to further understand breach mechanisms in the future. To this day, an engineer can travel to Teton Dam and compare as-built drawings from the 1960s and 70s to fully breached cross-sections of the earthen embankment, and visualize and better understand the mechanisms that led to its failure more than forty years ago (Photo 6).

Examples of Memorialized Dam Sites

Not every breached dam site warrants commemoration. Dam owners may be in litigation if injuries or fatalities resulted from an incident, and may want to reestablish benefits the dam provided prior to collapse. Private landowners may not be willing to provide access to property for liability, security, or other reasons. Public dam owners may have agency or bureau regulations and policies that further complicate establishment of a memorial site. Access and safety concerns for potential visitors at failed dam sites may add difficulties, and if located in a significant drainage, future flooding concerns would need to be addressed. Funding may not be available for additional construction and operation and maintenance associated with a facility. Many, if not most, dam failure sites aren’t significant enough to warrant the effort to memorialize them.

Despite these challenges, there are many ways to recognize dam failure sites. The table below shows a wide range of examples from museums and interactive exhibits to more cost-conscience plaques and markers. Some sites have the failed dam remnants still in place, while others have since removed the debris associated with the breach. A few dam failures sites have been converted into parks, where visitors may travel for reasons unrelated to the dam, increasing the likelihood of continued maintenance and funding. Many significant dam failures are also memorialized through various media platforms, including books, videos and websites.

Table 1. Examples of Commemorated Dam Failure Sites in the United States.

| Dam | Location | Year | Fatal-ities | Dam Failure Significance and Site Commemoration |

| South Fork | PA | 1889 | 2,209 | The deadliest dam failure in U.S. history, South Fork Dam and the resultant Johnstown Flood have the most extensive commemoration of any dam failure site in the U.S. including a National Memorial, Flood Museum, and a dedicated Cemetery. The ruins of South Fork Dam were kept in place and are still visible (Photo 8). |

| Austin (Bayless) | PA | 1911 | 78 | The dam failure site was added to the National Register of Historic Places (#86003570) in 1987. In 1994, the Austin Dam Memorial Park Association was formed and has since worked to preserve the dam remains and created the Austin Dam Memorial Park (Photo 9) |

| St Francis | CA | 1928 | 434+ | The infamous monolith left standing in 1928 was removed shortly after the dam failed. A few months after the failure, an 18-year old fell to his death from the large block [11], highlighting difficult decisions that dam owners might face following a dam failure, weighing safety against historic preservation (Photo 10). While little was done immediately after the failure, there has been a recent push, primarily led by the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, to memorialize the dam site. Signed into law on March 12, 2019, the Natural Resources Management Act establishes the Saint Francis Dam Disaster National Memorial and National Monument for the purpose of honoring the victims of the failure, to be managed by the National Forest Service. |

| Castlewood Canyon | CO | 1933 | 2 | The broken dam remains in place, located within Castlewood Canyon State Park, a day-use park with canyon trails, picnicking, rock climbing, and nature exhibits, bringing many more visitors than a strictly failed dam site would. Information related to the dam is available at the visitor center, including books, pamphlets, and survivor accounts of the events surrounding the failure (Photo 11). |

| Spaulding Pond | CT | 1963 | 6 | The dam was rebuilt by 1965, but the memorial in Mohegan Park was not installed until 2006 [12]. Spaulding Pond is an example that even if a dam is reconstructed it can still be memorialized, and it’s never too late to do so. It also demonstrates the healing that can accompany memorialization (Photo 12). Uniquely, the ‘Tree of Life’ where victims caught in floodwaters clung on to survive (Photo 13), is in the process of also being memorialized [13]. |

| Baldwin Hills | CA | 1963 | 5 | The dam site is now a grassy basin in Kenneth Hahn State Recreational Area, overlooking downtown Los Angeles. Portions of the dam are still discernible on the north end of the embankment [14]. The park is one of the largest open spaces in greater Los Angeles, with hiking trails, and baseball and soccer fields (Photo 14). |

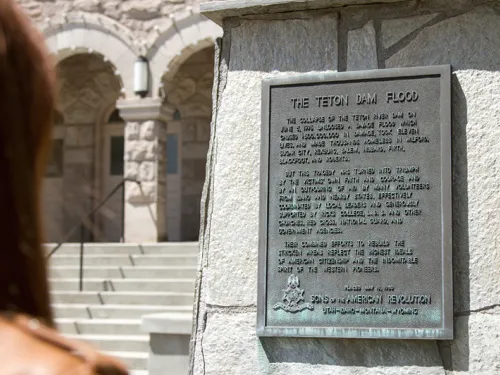

| Teton Dam | ID | 1976 | 11 | Likely the most studied event among dam safety professionals, the Teton Dam failure was a catalyst for national dam safety legislation. Much of the impressive 305-foot-tall breached embankment remains in place. The Museum of Rexburg houses an extensive Teton Flood Exhibit including films, photos, and memorabilia from the flood. (Photo 15) |

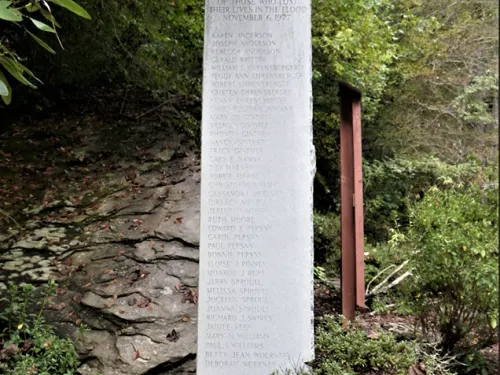

| Kelly Barnes | GA | 1977 | 39 | The Kelly Barnes Dam failure garnered national attention and had a significant impact on dam safety laws in the U.S. Following the failure, President Carter approved funding for dam inspections, and it eventually led to the creation of the Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) [15]. The dam site is located above Toccoa Falls, a popular waterfall above Toccoa Falls College. Although access is not allowed to the original dam site, where grass and trees have covered the remains, there is a memorial plaque located near the base of the falls, erected by the Toccoa Fall’s class of 1986 (Photo 16). Additionally, a commemorative marker describing the flood event was installed in 2017. The hydroplant, although abandoned, is maintained as a historical site and has a plaque, yet no mention of the dam failure. |

| Lawn Lake | CO | 1982 | 3 | The National Park Service (NPS) removed the failed dam in 2000 [16], but the natural lake remains, and can be accessed by hiking the Lawn Lake Trail, nearly twelve miles out and back from a parking area within Rocky Mountain National Park (Photo 17). The trail follows the Roaring River, where the downstream inundation path is obvious; the scoured earth is lined with large boulders, debris, and broken trees (Photo 18). There is no information at the dam or along the trail related to the dam failure. Where the floodwave exited the steep canyon into the valley floor, the flood debris forms an impressive alluvial fan of massive boulders. Near the boulders is a short path and interpretive site that describes the flood and timeline of events (Photo 19). A video was developed for NPS using this event to showcase the need for dam safety in National Parks. |

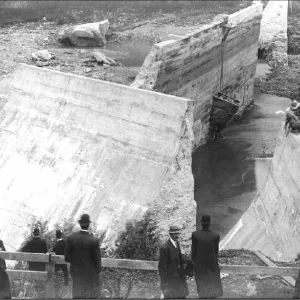

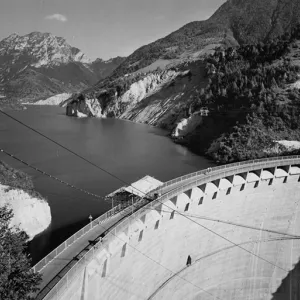

In addition to these examples in the U.S., there are several known memorialized dam sites abroad, with two of the most impressive sites located in Italy - Vajont and Gleno Dams. Vajont Dam technically didn’t fail, but in 1963 a massive landslide displaced essentially the entire reservoir downstream, killing over 2,000 people. The nearly 900-foot tall dam remains in place, still one of the tallest in the world, with the landslide clearly visible from the dam, and includes a memorial and museum. The Vajont Museum is even accessible virtually, where website visitors are able to electronically move around within the museum and view historic photos and exhibits (Figure 20). Gleno Dam, which failed in 1923 killing 356 people, also remains in place. The breached concrete arch buttress dam against the rugged Italian Alps backdrop makes for a dramatic memorial site (photo 21).

Conclusions and Recommended Best Practices

There is No 'One Size Fits All' Solution

In certain cases, dam failure sites can provide numerous benefits that may not be immediately obvious following a catastrophic dam failure. While each situation will have unique challenges, sites can be memorialized in many unique ways.

• There is no prescriptive approach to commemorating dam failure sites, and each case should be considered independently.

• There should be a certain significance or fatalities associated with the failure to warrant memorializing the site.

• Upkeep and maintenance should be considered with any commemoration effort. It would be a disservice to victims to construct a memorial only to let it fall into disrepair.

• When properly designed, sites may stimulate local economies and introduce communities to nearby historical events.

• Virtual memorials can be an alternative to constructing physical sites, can provide more information than a simple plaque, are more economical, and are likely to be viewed by a greater audience. However, a physical memorial can improve awareness of the site and improve understanding for those who visit a virtual memorial.

Sites Need a Champion

Dam failure sites in the U.S. show commemoration across a wide range of consequences, from two to over 2,000 fatalities, some with historical implications that were instrumental for dam safety legislation, and many recognized effectively with museums and monuments. There are many sites worth visiting across the U.S., but still many significant failure sites are not recognized to the extent in which they could be. For example, Williamsburg Dam failed in 1874 causing 139 fatalities, yet the remains of the structure are lost in trees and vegetation (Figure 22). The local historic society has artifacts and a few records, but there is no interpretive center, statues, or other high visibility facilities. A historic trail with information about various sites at the dam and in the downstream valley would be a great memorial and community asset.

• Historical societies and local advocacy groups often pave the way to memorialization, and should be key partners. In these cases, however, the engineering or dam safety aspects of the events may not be highlighted or considered.

• Recommendations for memorials should be included any time a dam failure investigation is undertaken.

• Development of a national failed dam advocacy group may be considered.

If Dam Failure Sites Aren’t Memorialized, They Risk Being Forgotten

Dam failures and incidents are unfortunate events for all involved, yet it is far worse for a failure to occur and the lessons not be learned, and memories be lost or forgotten. Remnants of a failed dam can be a part of understanding history. It’s not just the mechanics of failure we can learn from, there’s value in remembering and honoring the stories of survivors, heroes, and those who didn’t survive, all the while raising dam safety awareness in the U.S.

“…all of the survivors and eyewitnesses who came to remember in 2003 have died, but the indifference survived and the depths of San Francisquito Canyon remained isolated and remote. One late afternoon in 2013, I walked along an abandoned two-lane road until I arrived where the St. Francis Dam once stood. At first there were few signs the wall of concrete ever existed, but when I continued a short distance into the underbrush, half-hidden outcroppings of rubble appeared. Looking at the hillside I could identify faded scour marks, left decades before by a flood surge 140 feet high. A great tragedy happened here. It was hard not to wonder who or what was responsible, how it happened, why such a deadly disaster was so quickly forgotten, and whether there are urgent lessons yet to be learned.” [1]

References:

(1) Wilkman, J. (2016). Floodpath: The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th-Century America and the Making of Modern Los Angeles. Bloomsbury Press.

(2) McCullough, D. (1968). The Johnstown Flood: The Incredible Story Behind One of the Most Devastating Disasters America Has Even Known. Simon & Schuster.

(3) ASDSO. (2019). The Cost of Rehabilitating our Nation’s Dams: A Methodology, Estimate & Proposed Funding Mechanisms. Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

(4) ASCE. (2017). Infrastructure Report Card. American Society of Civil Engineers.

(5) ASDSO. (2020). Dam Failures and Incidents Webpage. Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

(6) Graham, W.J. & Brown, C.A. (1982). The Lawn Lake Dam Failure: A Description of the Major Flooding Events and an Evaluation of the Warning Process.

(7) PBS. (2016). Colorado Experience: Big Thompson Flood [Video]. Public Broadcasting Service.

(8) Petroski, H. (1985). To Engineer is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design.

(9) NPS. (2015). Great Falls of the Potomac. National Park Service.

(11) Rogers, D.J. (n.d.). Reassessment of the St. Francis Dam Failure [Presentation].

(12) Moody, Jr., T. (2013). A Swift and Deadly Maelstrom: The Great Norwich Flood of 1963, A Survivor’s Story.

(13) Steinhagen, J. (2014). Survivors pay tribute to life-saving tree. Hartford Courant.

(14) The Center for Land Use Interpretation. (2020). Baldwin Hills Dam Failure Site.

(16) National Parks Service. (2020). Let the Healing Begin. Rocky Mountain National Park High Country Headlines, 9(3).

(17) Wooten, R.L., Spangenberg, P.L., Salomaa, W.C., & Misslin, M.D. (2014). The Williamsburg Reservoir Dam Failure of 1874. ASDSO 2014 Annual Conference Proceedings. Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

(18) Sharpe, E. (2004). In the Shadow of the Dam: The Aftermath of the Mill River Flood of 1874.

This lesson learned was peer-reviewed by Mark Baker, P.E., DamCrest Consulting; Mike Hand, P.E., WYOH2OPE; and Wayne Graham, Bureau of Reclamation (retired).

Austin (Bayless) Dam (Pennsylvania, 1911)

Baldwin Hills Dam (California, 1963)

Castlewood Canyon Dam (Colorado, 1933)

Columbia River Levees at Vanport (Oregon, 1948)

Fujinuma Dam (Japan, 2011)

Hebgen Dam (Montana, 1959)

Kelly Barnes Dam (Georgia, 1977)

Lawn Lake Dam (Colorado, 1982)

Sheffield Dam (California, 1925)

South Fork Dam (Pennsylvania, 1889)

St. Francis Dam (California, 1928)

Swift and Two Medicine Dams (Montana, 1964)

Teton Dam (Idaho, 1976)

Vajont Dam (Italy, 1963)

Val di Stava Dam (Italy, 1985)

Infrastructure Report Card

Reassessment of the Castlewood Dam Failure

The Williamsburg Reservoir Dam Failure of 1874