Columbia River Levees at Vanport (Oregon, 1948)

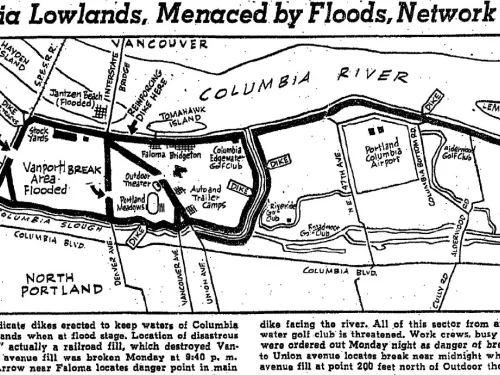

Vanport, Oregon occupied the marshy lowlands between the southern bank of Columbia River and the Columbia Slough. Located just north of Portland, and across the river from Vancouver, Washington; Vanport started as a private housing project constructed in a matter of months in 1943 by Henry Kaiser to house thousands of workers who flocked to his Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation during World War II. It became the largest wartime housing project in the United States and Oregon’s second largest city with a population of 42,000 at its peak during the war. While the population decreased after the war, returning service personnel helped stabilize the population at about 18,000 in 1948. Because Vanport was outside Portland city limits, a housing authority was created that served as the unofficial city government and oversaw creation of an independent fire district and school district for Vanport. The Multnomah County Sheriff’s Department provided law enforcement.

A system of levees (referred to as dikes at the time) totaling 4.9 miles in length protected the 650 acres of Vanport from flooding on all four sides. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) completed the system in 1941 under the Flood Control Act of 1936 and turned the project over to the Peninsula Diking District Number 1. A flood wall along the Columbia River to the north and a levee along the Columbia Slough to the south were constructed by USACE to protect the area that would become Vanport from flooding. Levees on the east and west of the protective quadrangle were not improved at the time. The existing Denver Avenue road embankment served as the eastern levee, and at the west was an existing railroad fill of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway that functioned as a protective levee (Maben, 1987).

In the spring of 1948, cold temperatures prevailed in the Columbia Basin through the spring into May, and in mid-May, temperatures increased rapidly and remained high. The cold temperatures into May delayed snowmelt in the basin that typically started in April until late May. When two major rainstorms moved through the basin in late May (May 19 to 23 and May 26 to 29, 1948), rainfall combined with snowmelt to fill the tributaries feeding the Columbia River, creating high water levels not seen since the record flood of 1894 (USGS, 1949).

By Tuesday, May 25, 1948, both the Columbia and Willamette Rivers reached 23 feet (eight feet above flood stage). Officials in Vanport started a 24-hour patrol of the north and south dikes and added the western dike (railroad fill) to the patrol when rising waters of Smith Lake reached it (Maben, 1987).

At a meeting at Red Cross headquarters on Saturday, May 29, 1948, the possibility of evacuation was discussed by the housing authority, USACE engineers, the Red Cross, the Sheriff, and other local officials. The housing authority and Red Cross estimated that together, they could provide emergency housing for 9,000 to 10,000 people (American Red Cross, 1948). Many of Vanport’s 18,000 residents relied solely on public transportation, further complicating evacuation planning. No decision was made to evacuate, and a follow-up meeting was scheduled for Monday, May 31, 1948. The housing authority’s recorded account of the meeting leaves the impression that evacuation would have been ordered if authorities had believed that sufficient housing could have been found. (Maben, 1987)

Early on the morning on Sunday, May 30, 1948 at 4:00 a.m., the housing authority issued a bulletin to Vanport residents and placed a notice under each door. The bulletin stated “…the flood situation has not changed…barring unforeseen developments, Vanport is safe….” and should it be necessary to evacuate, “the Housing Authority will give warning at the earliest possible moment” by continued siren and air horn. Sound trucks would give instruction. The bulletin concluded with: “Remember: Dikes are safe at present. You will be warned if necessary. You will have time to leave. Don't get excited” (Maben, 1987).

Shortly after the bulletin was distributed in the early morning of May 30, Robert English, Captain of the Vanport Fire Department, reported for duty at 7:30 a.m. For the previous two days, he and the rest of the Fire Department crew had been conducting 24-hour patrols of the dikes around Vanport in 4-hour shifts. Chief Engineer C.I. Haviland had instructed them to look for possible weak spots and gave instruction on how to identify them: blisters, heavy seepage, muddy water, boils, and unauthorized persons around the dikes after dark. A boil on the toe of the south dike and another leak coming under the flood wall at the north were sand-bagged and reported immediately to Mr. Haviland. That Sunday morning, as English started his patrols for the day, he and the others on patrol were warned that the river was rising rapidly and to be extremely cautious during their patrols.

At 9:15 a.m. on Sunday, May 30, English received a call at the Fire Station from Melvin Hall, who reported muddy water leaking under the railroad dike at the northwest corner of Vanport, near the intersection of Meadows and Broadacre Streets on the Vanport College campus. English rushed to the spot and met with three railroad officials and an engineer from Swift & Company. Upon the engineer’s suggestion to sandbag on the Vanport side of the dike, English reported the spot to the Assistant Fire Chief, who then ordered sandbags and workmen to the spot immediately. Workers identified another boil at 9:45 a.m. near Denver Avenue and Cottonwood, near the southwest corner Vanport.

At 10:15 a.m., English was notified that the break at the railroad dike was growing worse, and he sent a team of 10 to 12 men to the scene of the leak. At about 1:30 p.m., more men were sent to work on the railroad dike as it was still leaking badly. English stated, “We were still being assured of, at intervals, that there was no immediate danger, and I was passing the same information to worried residents as they were calling in continuously to get the latest reports” (English, undated).

At 3:00 p.m., Chief Engineer Haviland came to the Fire Station and ordered English to call the fire department personnel back to the Station immediately and English did so.

At 4:17 p.m. on Sunday, May 30, 1948, the railroad fill that separated Vanport from Smith Lake to the west broke, sending waves of water into the city. At 4:20 p.m., English reported hearing a shout outside the Fire Station that the dike had broken at the railroad dike where the crews had been sandbagging all day. He then heard the sirens from the Sheriff’s and Fire Chief’s rigs. English attempted to turn on the air horn, but water shorted it out and it would not work.

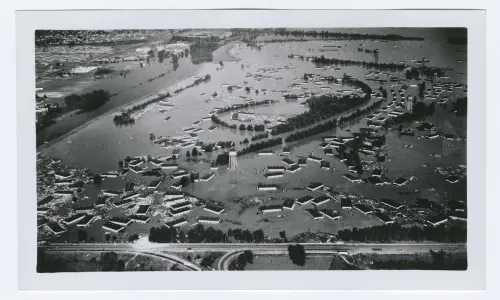

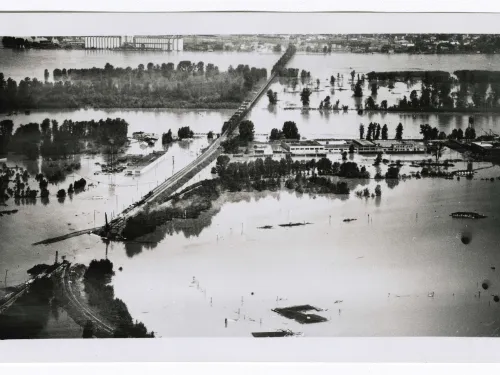

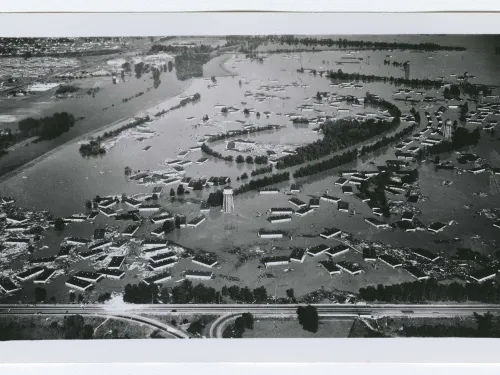

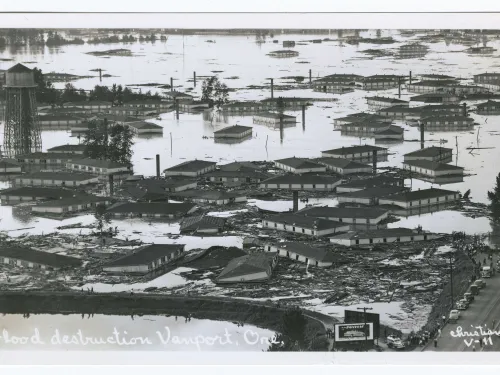

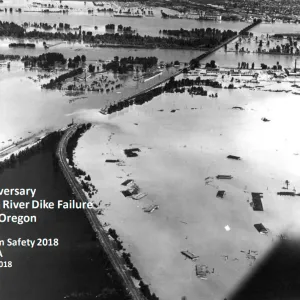

What began as a small hole in the railroad fill — initially just six feet in diameter — rapidly expanded, until water was steadily streaming through a 500-foot gap in the fill. The railroad fill at this location was 125 feet wide at the base with a 75-foot top width (Maben, 1987). Just 30 minutes before the dike broke, the army engineers noted Vanport was 15 feet below the water level in the Columbia River and adjacent Smith Lake. When the railroad fill broke, water from Smith Lake rushed in, and the first wave hit the first row of houses within a minute after the warning siren shrieked (Oregonian, May 31, 1948). As a 10-foot-high wave of water rushed through Vanport, it knocked the wood buildings off their foundations, popping many of them apart. Fortunately, the water initially filled the adjacent sloughs, providing some attenuation of floodwaters and allowing residents precious minutes to evacuate. Electricity in Vanport went off at 4:50 p.m. Water swirled around the two radio towers in Vanport's northeastern section, and the station left the air at 5:21 p.m. A half-hour later, a floating apartment building crashed into one of the towers and toppled it.

Within an hour after the disaster, Oregon Governor John H. Hall declared a state of limited emergency and authorized the national guard to requisition materials and personnel as needed. According to The Oregonian, “the injured were too numerous to count; all available ambulances were mobilized and kept up a steady shuttle service to nearby hospitals” (1948, May 31).

Portland Traction Company buses arrived to evacuate Vanport residents, but it soon became clear that boats were needed to rescue people. The Sheriff issued an emergency call for boats and many arrived quickly. As the water continued to rise, children were tossed from the upper floor windows of the housing units to the rescue boats below. Soon the boats took people directly from the roofs of the two-story units. By 9 p.m. search crews believed no one was still stranded.

Daylight dawned on Monday, May 31 and no fatalities had been discovered. As the day wore on, the Denver Avenue road embankment at the east side of Vanport became a focus of concern. It breached just after 9 p.m. on Monday, May 31 at the Vanport underpass. An emergency vehicle with one occupant was traveling over Denver Avenue when the road collapsed, and the vehicle disappeared in the water. This was the first confirmed fatality in the Vanport flood. As the wall of water pressed further east past Vanport, the Union Ave road embankment also breached.

In less than a day, the nation’s largest housing project – and Oregon’s second largest city – was destroyed. More than 18,000 residents were left without homes, and many were injured. At least 15 people perished in the Vanport flood and the State estimated $21,500,000 in property loss. At the time of the flood, Vanport was home to about 12,600 Caucasians, 5,000 African Americans and 900 Japanese Americans (American Red Cross, 1948). It was easily the most diverse community in the state.

On Tuesday, June 1, 1948, the Columbia River crested at 30.2 feet and began receding. The river receded so slowly that Vanport was not uncovered for weeks. It would be months before the official death toll would be announced. Thirteen bodies were identified by September 1, 1948, three months after the dikes broke. The Multnomah County Coroner’s official list of bodies recovered was eventually set at 15 with the acknowledgement that there may have been other victims whose bodies were never discovered.

In the days after the flood, it was reported in the local newspaper that the breached railroad fill was not designed or constructed to function as a levee; it was a railroad fill constructed in 1907 to support tracks of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle (SP&S) railway. SP&S maintained the fill but acknowledged that it was maintained as fill to support the tracks, not as a dike to withstand floodwaters. Leading up to and during the flood, this section of the diking system was believed to be the strongest, with a top width ranging from 40 to 60 feet, and the largest amount of freeboard of the entire diking system. The Oregonian reported, “The failure occurred within the fill because its extremely high freeboard prevented water from going over the top.” (1948, June 1).

A theory about the failure of the railroad fill was advanced by an assistant maintenance engineer with the Portland housing authority assigned to the Vanport project. When originally constructed in 1907, the rail line originally crossed the lowland of present-day Vanport on a trestle and was later filled in, with the trestle left in place within the fill. A retired Chief Engineer for the railroad confirmed that the trestle was filled in about 1913. The railroad engineer doubted trestle deterioration caused the break, while the housing project engineer maintained that the wood in the fill likely compressed and caused movement in the fill.

The Vanport railroad fill, and the levees on Denver and Union Avenues that failed subsequently, appear to have failed due to internal erosion that manifested with hydrostatic loading from an extreme flood event.

After the Vanport floods, the attorney for the housing authority was quoted in the press saying “The housing authority feels terribly, terribly bad that lives possibly were lost, but all you can do is depend on the advice of competent engineers.” (Maben, 1987). The housing authority and USACE engineers became scapegoats for the disaster, as residents filed over 650 liability suits seeking damages. Ultimately, in October 1952, after years of investigation and court battles, Judge James Alger Fee found that the government shall not be held responsible for flood damages and the plaintiffs lost all cases.

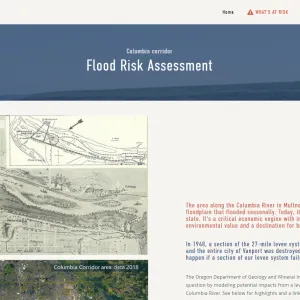

At the time of the flood of 1948, USACE was developing a comprehensive plan for the Columbia River basin that focused primarily on navigation and power production. The flood of 1948 highlighted the need for flood control on the Columbia River, and as a result, USACE’s comprehensive plan for the basin came to include flood control (Billington and Jackson, 2006).

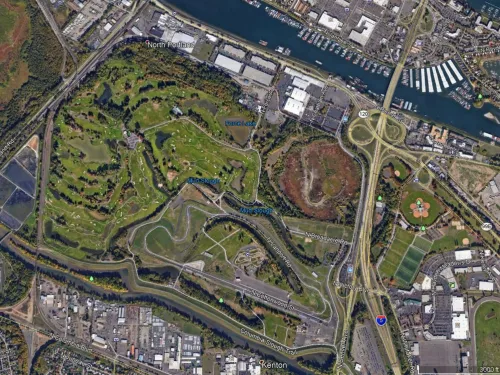

Today, the area of Vanport is owned by the City of Portland and is primarily used for recreation and industrial businesses. Homes no longer occupy this stretch of marsh between the Columbia River and its parallel slough. A public golf course occupies much of what was Vanport, along with the Portland International Raceway, an Expo Center, with wetlands and small ponds interspersed. Historical markers near the golf course and raceway tell the story of Vanport, a city washed away overnight by the Columbia River.

References:

(1) American Red Cross, Portland-Multnomah County Chapter. (1948). Vanport City Flood Preliminary Disaster Report. Accessed via Multnomah County Library, Portland OR.

(2) English, R.O. (N.D.). My Observations of the Vanport Tragedy – the Flood. Oregon Historical Society.

(4) Maben, M. (1987). Vanport. Oregon Historical Society Press.

(5) DOGAMI. (2018). Special Paper 50: Flood Risk Assessment for the Columbia Corridor Drainage Districts in Multnomah County, Oregon. Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries.

(6) Abbott, C. (2020). Vanport. The Oregon Encyclopedia.

(7) Oregonian. (1948, May 31).

(8) Oregonian. (1948, June 1).

(11) Billington, D.P., & Jackson, D.C. (2006). Big Dams of the New Deal Era: A Confluence of Engineering and Politics. University of Oklahoma Press.

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by Steve Durgin, P.E., Natural Resources Conservation Service (Retired).

Lessons Learned

Dam failure sites offer an important opportunity for education and memorialization.

Learn more

Dam incidents and failures can fundamentally be attributed to human factors.

Learn more

Emergency Action Plans can save lives and must be updated, understood, and practiced regularly to be effective.

Learn more

Floods can occur due to unusual or changing hydrologic conditions.

Learn more

Regular operation, maintenance, and inspection of dams is important to the early detection and prevention of dam failure.

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn moreAdditional Lesson Learned Information

- Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency. Because flooding of Vanport was believed to be unlikely, few steps were taken to prepare for evacuation of more than 18,000 people, many of whom relied on public transportation. The absence of warning time forced Vanport residents to flee without any of their possessions or property. The breach occurred during a pleasant Sunday afternoon on a holiday weekend, which resulted in fewer deaths related to the floods, as many families had already left their homes to enjoy the weather.

- Emergency Action Plans can save lives and must be updated, understood, and practiced regularly to be effective. The flood caught the community of Vanport without a comprehensive disaster plan. During the disaster, traffic crowded the limited evacuation routes and hindered emergency response efforts. At least two of the dike failures were on road embankments that served as major north-south evacuation routes. Many of the residents expressed their reliance on the siren system, which did not operate at peak performance during the disaster. The housing authority and Red Cross scrambled to stand up additional emergency radio operations as the floods knocked out electricity and communication systems, further hindering the disaster response.

- Dam failure sites offer an important opportunity for education and memorialization. Vanport has been wiped from the map but historical markers in the area remind visitors of the community’s legacy and its influence on the city of Portland today.

- Regular operation, maintenance, and inspection of dams is important to the early detection and prevention of dam failure. Unclear responsibility about the operation and maintenance of the railroad fill as a part of the Vanport diking system contributed to an assumption by many that this segment of the dike was the strongest, when in fact, it was not designed to function as a dike.

- Dam incidents and failures can fundamentally be attributed to human factors. The decision not to evacuate Vanport cost people their lives and belongings. The account by Robert English demonstrates the issue at the railroad fill was first observed about 7 hours before failure and grew more concerning as the day progressed. Failure of the railroad fill was likely inevitable; the loss of life could have been reduced or avoided by evacuating Vanport on Sunday early afternoon, as the fill showed signs of failing.

Additional Lessons Learned (Not Yet Developed)

- Implementation of land use planning can reduce the consequences of failure. Henry Kaiser hastily constructed Vanport as temporary housing in response to the needs of the war effort. Sufficient long-term flood control efforts in the Columbia River basin were not yet in place. The consequences of levee failure were high, given the population protected by the Vanport levee system. During the peak of the city’s occupancy, as many as 42,000 people lived at risk from flooding. Following the 1948 flood, the decision to change the land use in the area and not rebuild the city greatly reduced the risk of loss of life due to flooding.

70th Anniversary of the Columbia River Dike Failure

Columbia River Images

Evaluation and Monitoring of Seepage and Internal Erosion

Flood Risk Assessment for the Columbia Corridor Drainage Districts in Multnomah County, Oregon

Levee Safety Program Website