Swift and Two Medicine Dams (Montana, 1964)

Introduction

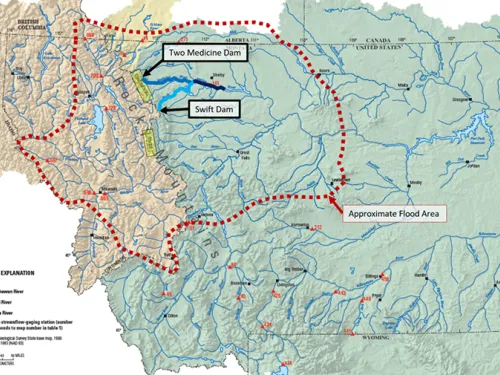

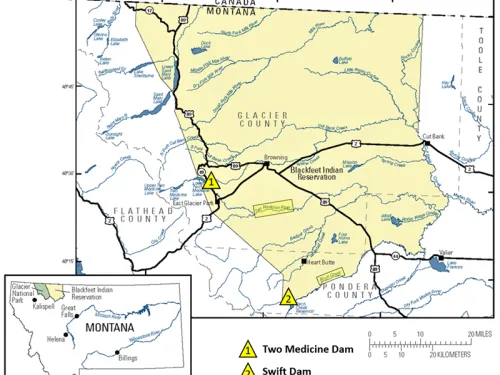

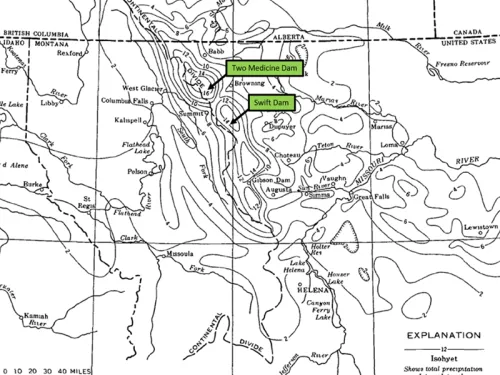

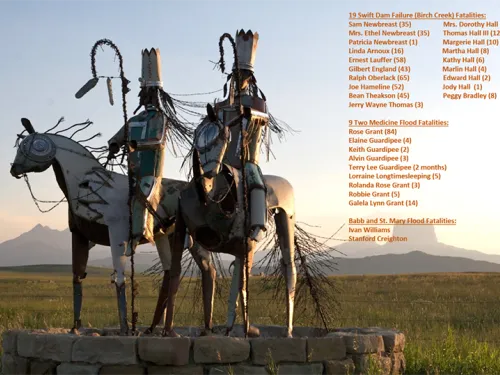

The second week of June 1964 brought one of the worst natural disasters in Montana’s recorded history. In all, the flooding caused 30 deaths, upwards of $60M in damages (over $500M in 2020 dollars), and exceeded many of the peak flow records across the state [USGS, 1967]. While much of the media coverage of this event focused on flooding in more populated areas, like Great Falls and Kalispell, all of the fatalities from the flood occurred on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, where the Swift and Two Medicine Dams failed (Fig. 1 and 2).

The 1964 Flood

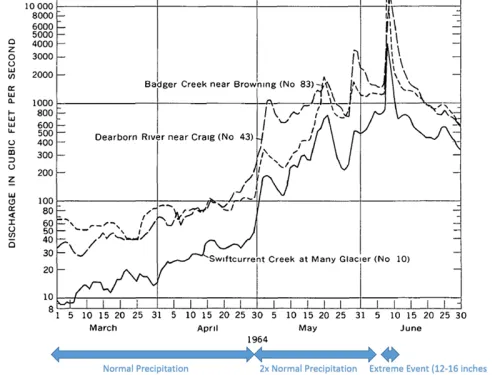

Northwestern Montana began the year with normal precipitation levels from January through March 1964. Heavy snowfall in April brought mountain snowpack to well above average by the end of the month. In early May, an unusually heavy storm dumped record snowfall. In addition to the substantial snowpack, below normal temperatures from March to May delayed runoff. By the end of May, mountain soils along the Continental Divide were nearly saturated, and antecedent conditions were prime for flooding (Fig. 3) [USGS, 1967].

By early June, warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico was moving northwest over the western plains and central Rocky Mountains. When this mass contacted the Continental Divide (with peaks of 7,000 to 9,000 feet in elevation) orographic lifting caused a storm of nearly unfathomable magnitude, producing an intense, high-volume rain on snow event [Parrett, 2004]. Precipitation during the 36-hour storm period, June 8-9, 1964, recorded from 12 to 16 inches in the basins above Swift and Two Medicine Dams, respectively (Fig. 4), and caused the most severe floods of record on both sides of the Divide [USGS, 1967]. Estimates suggest a 5,000 to 10,000 or more year return period for the storm event [HMR 55A, 1988 and Costa and Baker, 1981].

The area affected by resultant flooding covered nearly 30,000 square miles, or about 20% of the state of Montana. By Thursday, June 11, President Lyndon Johnson had declared nine counties in northwest Montana a federal disaster area [Parrett, 2004].

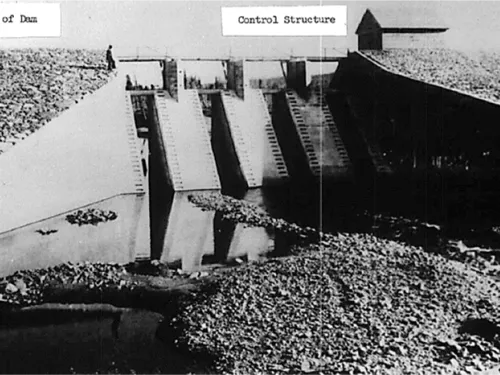

Swift Dam Failure

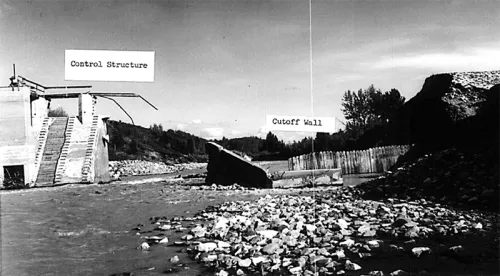

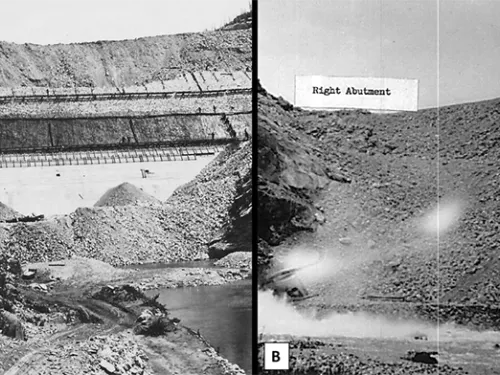

Swift Dam was constructed along Birch Creek on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, just east of the Continental Divide, from 1912 to 1914. A privately-owned and operated irrigation structure, the dam was constructed along with a series of canals and diversions, providing irrigation water to 93,000 acres both on- and off-reservation. The dam was a 157 foot tall, rockfill structure, covered on the upstream face with a concrete slab and on the downstream face with compacted earthfill. The dam had a contributing drainage area of 185 square miles and a reservoir storage capacity of 31,000 acre-feet. It had a concrete lined outlet tunnel, and an overflow spillway with a concrete lined channel, with an estimated discharge capacity of 10,000 cubic feet per second. The emergency spillway was excavated in rock on the left side (Fig. 5) [BIA, 1964].

The 50 year old dam failed on June 8, 1964 at about 10:10 a.m. Many of the Reservation’s 6,500 residents lived near the creek bottoms that provided convenient grazing, shade, and water for livestock and a ready supply of firewood and timber [BIA, 1964]. There were no witnesses to the failure, and no timely warnings were issued prior to dam failure, despite last-minute efforts of a local radio station to broadcast a warning message [Graham, 2014]. The failure of Swift Dam was responsible for 19 deaths, all on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation.

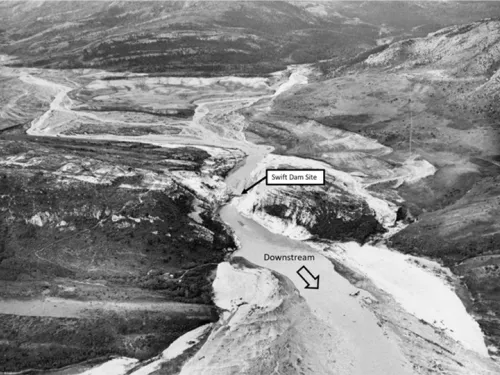

Osmun [2014] concluded that the significant inflows likely exceeded the spillway capacity, causing water to overtop the embankment, probably eroding downstream earth/rockfill which served to “buttress” the upstream concrete face. Erosion of the downstream face probably then led to headcutting and failure of the concrete on the upstream face. With reduced resisting force, some of the dam may have slid downstream. Evidence to support this sliding includes several large blocks of rockfill material that were moved a quarter to half mile downstream without being broken up (Fig. 7) [USGS, 1967].

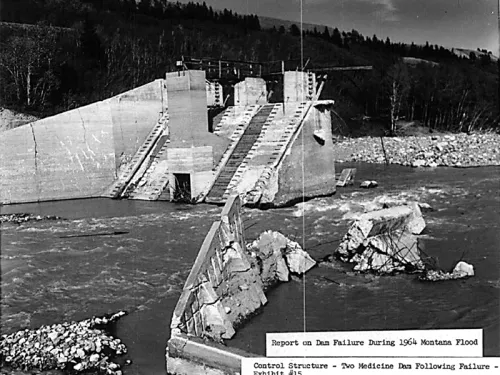

Two Medicine Dam Failure

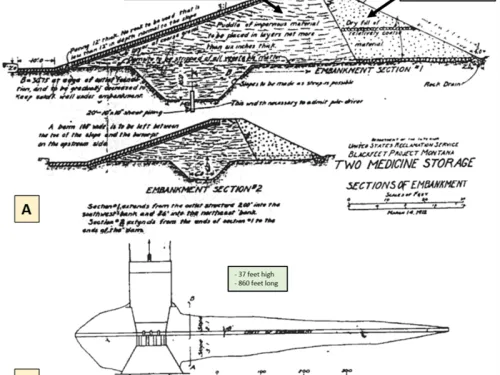

Two Medicine Dam was designed by the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) as part of the Blackfeet Irrigation Project, and was constructed from 1911 to 1913. The dam was 37 feet high, 860 feet long (Fig. 9) and stored 16,000 acre-feet. It had a slab and buttress reinforced concrete spillway with earthen embankment sections on both abutments. The discharge capacity of combined spillway and outlet works was 5,500 cubic feet per second (Fig. 10-11).

Two Medicine Dam also failed on June 8, 1964 around 6 p.m., about eight hours after Swift Dam. Like Swift Dam, the cause of failure is attributed to inadequate spillway capacity, with estimated inflows of 9,600 cubic feet per second. A Reclamation engineer visited the site shortly after the failure and wrote an internal investigation memo [Reclamation, 1964], which summarized the physical failure mechanisms. Based on those observations, the failure likely initiated at the contact between the earthen embankments and the spillway retaining walls. In these areas, there was indication of settlement of the embankment away from the wall, which likely created a low point and cracking, providing a preferential pathway for the high reservoir to begin erosion. Then the embankments on both sides of the spillway began to wash away. The greater portion of the erosion appears to have occurred on the right side, as evidenced by the collapsed counterfort wall on that side. Rockfilled timber cribbing downstream may have slowed the erosion and headcutting of flows back through the dam to the reservoir (Figs 12-17) [Reclamation, 1964].

Unlike Swift Dam, there were witnesses to the slow degradation of Two Medicine Dam, and the downstream population received what appears to be adequate warning time prior to failure. While there were no fatalities from the actual dam failure, nine deaths occurred due to downstream flooding prior to the failure. Tragically, a truck with 17 people stalled in the river below the dam, and after a harrowing rescue attempt, nine people did not survive; eight of them were children (video account of rescue). Successful evacuations and heroic rescues undoubtedly saved many lives downstream of Two Medicine Dam.

Conclusions and Lessons Learned

Reclamation designed new dams for both sites (Lower Two Medicine Dam completed in 1966; Swift Dam completed in 1967), and both remain in service today (Fig. 18, 19). There are many lessons to be learned from the tragic events surrounding the 1964 flood, and the consequent failures of these dams:

- Multiple dams can fail or be in danger of failing during a single flood event. which is what occurred during the 1964 flood. Swift and Two Medicine Dams failed the same day, and in addition, there were many other dam incidents during that week, where damage was suffered to structures, yet the dams performed as designed. In fact, many of these dams across the region actually reduced downstream consequences, saving lives and property, and attenuating flooding [USGS, 1967].

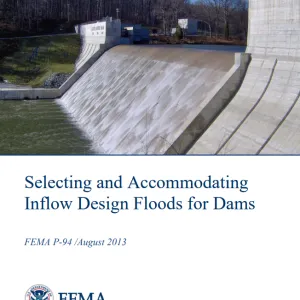

- High and significant hazard dams should be designed to pass an appropriate design flood, and existing dams should be assessed to make sure they have adequate spillway capacity. The failures of both Swift and Two Medicine Dams were initiated due to inadequate spillway capacity. Rain-on-snow events should be considered while evaluating inflow design floods. Extreme flood events do occur.

- Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during dam failures and incidents. The historic record of dam failures clearly shows that no warning or evacuation before failure can have a fundamental influence on loss and survival outcomes for people located in inundation zones, and the difference in fatalities between the Swift Dam failure (19 people) and the Two Medicine Dam failure (no fatalities after dam failure) validates this. Because Two Medicine failed later in the day (~6 p.m.) as compared Swift Dam (~10 a.m.), and because significant flooding had already been occurring downstream of Two Medicine Dam prior to its failure (flooding had already caused fatalities), warning was disseminated, in this case through unrehearsed radio broadcasts. Washed out bridges and damaged phone lines further complicated warning and evacuation attempts.

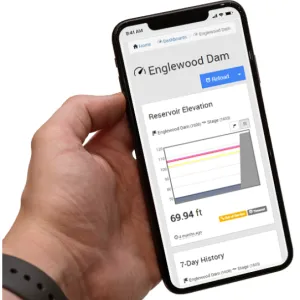

- Early Warning Systems (EWS) can provide real-time information on the health of a dam, conditions during incidents, and advanced warning of dam failure. There were no witnesses to the failure of Swift Dam, and often small, rural dams do not have on-site dam tenders. As noted above, if there had been some advanced warning of the pending dam failure and consequent flood wave, the loss of life could have been substantially reduced. In addition, during large regional storm events like the 1964 flood, an EWS can help prioritize limited resources to evacuate and rescue the population at risk.

- Non-breach consequences from operations or high-flow scenarios can exist for dams. The fatalities downstream of Two Medicine Dam occurred before the dam failed. Non-breach flooding should be assessed and communicated. Downstream flooding even when a dam does not fail, can hinder communication, evacuation, and assistance to those in need due to washed out infrastructure like roads and bridges, power, and lines of communication. Dam failure inundation maps and Emergency Action Plans (EAPs) should include non-failure inundation mapping. Downstream damages prior to a dam fully failing should be part of EAP exercise scenarios. Dam safety programs should collaborate with floodplain management professionals to reduce risk to downstream residents by discouraging development in floodplains downstream of dams.

- Significant dam failures and incidents warrant an independent forensic investigation which should include the human/organizational and physical factors that led to the incident or failure as well as the effectiveness of the EAP, warning and evacuation. A brief internal memo was completed on the Two Medicine Dam failure by Reclamation [1964], but the report included only the physical elements of the failure and was not shared widely. The report was also conducted by the designer of the dam (Reclamation), so its independence could not be assured. No formal forensic investigation was completed for the Swift Dam failure, however a document was prepared that includes accounts and interviews of flood survivors and employees that lived through the event, including details on the flooding and warning/evacuation on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation [BIA, 1964]. While a formal, independent forensic investigation made up of a team of recognized industry experts could have potentially developed and shared many lessons to be learned from these failures, possibly preventing future dam failures, without the reports that exist today, little would be known of this event.

- Dam failure sites offer an important opportunity for education and memorialization. Physical memorials have been constructed for the victims of the Birch Creek flood (Fig. 20, 21), and a compelling series of documentary videos were recently produced, which helps to ensure that this tragic event is remembered and the victims honored.

References:

(2) Costa, J.E. & Baker, V.R. (1981). Surficial Geology: Building With the Earth. Wiley.

(5) Osmun, D. (2014). Montana Floods of 1964: Failures of Swift Dam and Two Medicine Dams – June 8, 1964, Life Loss Tragedy on the Blackfeet [PowerPoint]. ASDSO 2014 Annual Conference. Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

(9) USGS (2020). Hydrologic Assessment of the Blackfeet Reservation, Montana. Wyoming-Montana Water Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Department of the Interior.

(11) WGBH (2019). The Blackfeet Flood [Video]. YouTube.

This case study summary was peer-reviewed by Dan Osmun, HDR, Inc.; Gene Onacko, BIA, Rocky Mountain Region; Mark Baker, DamCrest Consulting; and Mike Hand, WYOH2OPE.

Lessons Learned

Dam failure sites offer an important opportunity for education and memorialization.

Learn more

Downstream flooding can be caused by spillway flows that exceed channel capacity or as a result of reservoir misoperation.

Learn more

Dozens of dams can fail or be in danger of failing during a single event (i.e. swarming failures). Dam owners and regulators need to prepare for these types of events.

Learn more

Early Warning Systems can provide real-time information on the health of a dam, conditions during incidents, and advanced warning to evacuate ahead of dam failure flooding.

Learn more

Extreme floods do occur.

Learn more

Floods can occur due to unusual or changing hydrologic conditions.

Learn more

High and significant hazard dams should be designed to pass an appropriate design flood. Dams constructed prior to the availability of extreme rainfall data should be assessed to make sure they have adequate spillway capacity.

Learn more

Timely warning and rapid public response are critical to saving lives during a dam emergency.

Learn moreAdditional Lessons Learned (Not Yet Developed)

- Non-breach consequences from operations or high-flow scenarios can exist for dams.

- Significant dam failures and incidents warrant an independent forensic investigation.

A Decade of Learning from our Past and Preparing for our Future

Federal Guidelines for Selecting and Accommodating Inflow Design Floods for Dams

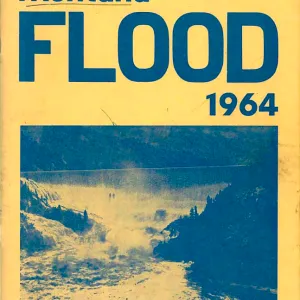

Photo Booklet – Montana Flood of 1964

Selecting and Accommodating Inflow Design Floods for Dams